Edna St. Vincent Millay took a single foray into the mystery genre before the Pulitzer Prize for her poetry turned her attention elsewhere. “The Murder in the Fishing Cat” remains a tantalizing glimpse into what might have been.

Edna St. Vincent Millay took a single foray into the mystery genre before the Pulitzer Prize for her poetry turned her attention elsewhere. “The Murder in the Fishing Cat” remains a tantalizing glimpse into what might have been.

Illustration: Richard Polt

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) was something of a Renaissance spirit. The first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, she was a celebrated voice of her generation whose candle burned at both ends and in the middle as well. In addition to her poems, she published stories under the pseudonym Nancy Boyd, wrote several plays and saw some of them produced, and acted alongside Eugene O’Neill as a member of the fledgling Provincetown Players.

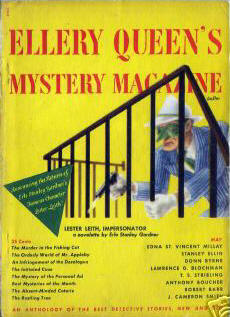

Her creative output also included a single mystery story, “The Murder in the Fishing Cat.” In a November 1922 letter, Millay told Norma and Charles Ellis, her sister and brother-in-law, that she had sent “Cat” to her agents, describing it as “a story about Paris,” and added, “I tell you, me and Eddie Poe—there’s no stopping us Americans.” The story first appeared in the March 1923 issue of Century Magazine and was republished in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in May 1950. It is likely that Millay wrote it sometime during the early 1920s when she was living in Europe.

"Fishing Cat” is the disturbing tale of a restaurant owner, Jean-Pierre, whose best days seem to be behind him. His wife has left him; his only waiter has been drafted into the army. His once-fashionable Restaurant du Chat qui Pêche (literally, the Restaurant of the Cat Who Fishes) is shunned, and he is reduced to watching the steady stream of customers patronize the new cafe now in vogue next door. Millay’s opening lines set a scene of defeat:

The popularity of a restaurant does not depend on the excellence of its cuisine or the cobwebs on the bottles in its cellar. And you might have in the window ten glass tanks instead of one in which moved obscurely shadowy eels and shrimps, yet you could be no surer of success. Jean-Pierre knew this, and he did not reproach himself for his failure. It is something that may happen to the best of us. (Century, p. 663)

The lonely Jean-Pierre develops a fixation on the sole occupant of his eel tank, which leads to unexpected, violent results and a singular twist at the end.

In addition to the superb depiction of an uneasy, skewed reality, other strengths of the story are Millay’s fluid description and affecting characters who bloom in the merest strokes against the colorless Jean-Pierre—a serious, impoverished little girl selling bright fistfuls of flowers, a kindhearted American youth who buys them, a selfish Parisian matron, Jean-Pierre’s frivolous wife. Millay’s lyrical gift for language also is evident, such as in this passage later in the story:

In the Restaurant du Chat qui Pêche the dusk thickened into dark, the darkness into blackness, and no lights came on. The door was wide open. The night wind came in through the door, and moved through the empty rooms. (Century, p. 675)

In August 1949, Millay told Ellery Queen (actually Frederic Dannay, one-half of the team of writing cousins) that the story was inspired by a lunch in Paris. “I turned my head,” wrote Millay to Queen, “and saw . . . just inside the window of the restaurant, a large glass tank containing water in which eels were swimming. I wished they were not there. The rest [of the story] was all imagination.” The Fishing Cat, she added, was an actual restaurant, although not located where she had placed it in her story.

Dannay was impressed with Millay’s effort. “In Miss Millay’s prose,” he wrote in the introduction to the “Fishing Cat” reprint in EQMM, “you will find the qualities of both herself and her poetry—the clear, precise voice and the delicate, almost fragile, image; the intensely personal style which is of simple beauty and beautiful simplicity; and the psychological probing of loneliness and mental fatigue, with their twisting emotional crosscurrents and undercurrents...”

Dannay was impressed with Millay’s effort. “In Miss Millay’s prose,” he wrote in the introduction to the “Fishing Cat” reprint in EQMM, “you will find the qualities of both herself and her poetry—the clear, precise voice and the delicate, almost fragile, image; the intensely personal style which is of simple beauty and beautiful simplicity; and the psychological probing of loneliness and mental fatigue, with their twisting emotional crosscurrents and undercurrents...”

In Dannay’s view, there was a particular reason for the strength of Millay’s mystery story: her position as a preeminent poet. “[P]oets, it has always seemed to us,” he noted in the EQMM introduction, “are peculiarly sensitive to the smell of evil, to the sounds of violence, to the sight of cruelty, to the touch of tragedy, to the taste of murder—and to that sixth sense which detects and diagnoses the heartache and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.”

Why did Millay write a mystery? The Library of Congress is currently recataloging Millay’s papers, but the material that is available sheds some interesting light on “Fishing Cat.”

Among her 1922 writings is an unpublished essay, “E.A.P.,” in which Millay discusses the verses of Edgar Allan Poe, referring to the Russian and French reverence for Poe’s poetry and the American acceptance of this foreign esteem. She, however, held a far different opinion. “At no point in the reading [of Poe’s poems],” she wrote, “was there produced in me that combined sensation of excitement and peace by what [sic] I know that I have found a poem. I remained throughout untouched . . . unconvinced.”

The essay coupled with the edgy story and the comment in Millay’s letter regarding “Eddie Poe” might suggest “Fishing Cat” was her attempt to “out-Poe Poe” in the short story form in which he excelled, similar to Charles Dickens’ effort with The Mystery of Edwin Drood to “out-Collins Collins”—his friend and successful sensation writer Wilkie Collins.

It is likely Millay wrote “Fishing Cat” for the money—her nine romances under the Nancy Boyd pseudonym in Ainslee’s paid far better than the small sums she was then earning for her poems. At about the same time Millay also was writing well-paid pieces for Vanity Fair. Because she was contributing to her mother’s support as well as her own, money would have been an important factor. Placing the story in Century Magazine was logical; Century under editor William Rose Benet had previously published her poem “Time Does Not Bring Relief.”

Just one month after “Fishing Cat” was published, Millay won the Pulitzer Prize and so turned in earnest to her poetry. For mystery readers, “Fishing Cat” remains a tantalizing dip into possibility.

Where to read “Murder in the Fishing Cat”

In addition to the March 1923 Century Magazine publication and the June 1950 appearance in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, “Fishing Cat” is reprinted in Ellery Queen’s Poetic Justice (New York: New American Library, 1967) and The Poet’s Story, edited by Howard Moss (New York: Macmillan, 1973).

Acknowledgements

I thank Alice Lotvin Birney, literary manuscript historian, and Nan Ernst, archivist for the Edna St. Vincent Millay collection, the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; and John Harrelson for their assistance in the preparation of this article. Excerpt from the unpublished essay “E.A.P.” by Edna St. Vincent Millay. Copyright © The Edna St. Vincent Millay Society. Used by permission.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Spring Issue #79.