Tom Rob Smith's award-winning trilogy set in the former Soviet Union concludes with the January 2012 release of Agent 6.

Tom Rob Smith's award-winning trilogy set in the former Soviet Union concludes with the January 2012 release of Agent 6.

Mystery Scene first talked with Tom Rob Smith upon the publication of The Secret Speech, his follow-up to the highly acclaimed Child 44. Here is that 2009 conversation.

Soap opera stories about messy lives and sexual dalliances would seem to have little in common with Stalinist Russia’s bleak and brutal world. But the journey from soap operas to a critically acclaimed bestseller set in 1950s Russia has proven to be the right path for British novelist Tom Rob Smith.

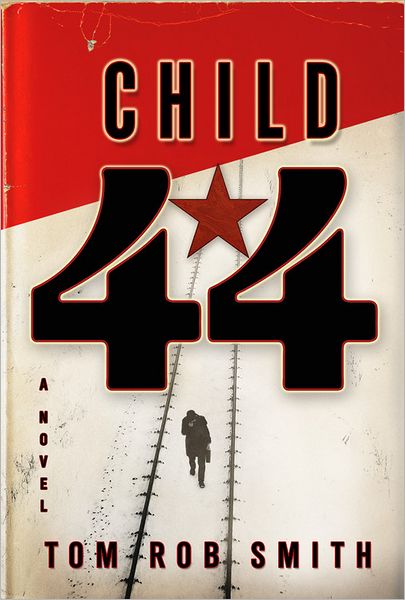

Smith’s debut crime thriller Child 44 follows Leo Demidov, a compromised member of Moscow’s security services, who risks his career and life to capture a prolific child killer. Child 44, the first of a trilogy, was awarded the 2008 Ian Fleming Steel Dagger for Best Thriller by the Crime Writer’s Association. It was also nominated for the 2008 Costa First Novel Award (formerly the Whitbread Prize), the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the Man Booker Prize. Child 44 made several best of the year lists and was a Barnes & Noble recommended book.

Leo and his wife, Raisa, return in the newly published The Secret Speech, set immediately after Khrushchev denounced Stalin before the Communist Party Central Committee in 1956. The Secret Speech is garnering as good if not better reviews than Child 44.

Not bad for a guy who recently turned 30 and who just a few years ago was part of a team coming up with story ideas for such British potboilers as Family Affairs, Bad Girls, and Dream Team.

Smith views this as a natural progression.

“I always loved stories and loved narratives. These were just another form,” said Smith during a recent telephone interview from his home in London.

“When I was much younger I wanted to be an astronaut, mainly because I liked the stories. But I had bad hearing and bad eyesight. Then I wanted to be an actor because of the stories, but I wasn’t much of an actor, either. So I finally worked out that I wanted to be the one coming up with the stories.”

Smith started writing in earnest when he was 16 and won a drama competition for a couple of short plays. By age 17 he had written his first full-length play and saw it produced.

“I remember the first time I sat in an audience and watched people react to what I had written. It was a turning point for me.”

The middle child of an English father and a Swedish mother, Smith was born in London where his parents ran a small antiques business. He spent his summers at his grandparents’ remote farm in Sweden where they were beekeepers. “They made the most incredible honey,” he remembers fondly.

The middle child of an English father and a Swedish mother, Smith was born in London where his parents ran a small antiques business. He spent his summers at his grandparents’ remote farm in Sweden where they were beekeepers. “They made the most incredible honey,” he remembers fondly.

Smith says he has “always been very head down in the books.”

When he graduated from high school, he won a place at Cambridge to study English literature. Instead, he delayed enrolling for a year to teach children English in a remote village in the Baglung region of Nepal at the foot of the Annapurna mountain range.

During his three years at St. John’s College Cambridge, he founded InPrint, a literary magazine still being published, and edited the May Anthologies, an Oxbridge collection of short stories. His play Losing Voices was produced by the prestigious Marlowe Society, the first student play it ever funded. After graduating in 2001, he combined a creative writing fellowship with a yearlong exchange position at Italy’s University of Pavia.

Like all college students, Smith needed a job after graduation. Enter the soap operas when Britain’s Channel 5 offered him a position as a writer and a script editor.

“When I came out of university, they were the only people to take a chance on someone who didn’t have that much experience. They were brilliant in that sense.”

As a teenager he “quite liked EastEnders [Britain’s most popular soap opera]. I didn’t have a burning passion, but I liked them.”

Smith’s stint on the soap operas was like a graduate course in writing.

“They craved a vast number of stories—five half-hour shows a week. That’s a colossal amount of stories to get through. They needed a big story team and would take on experienced stories editors and trainees. They don’t have a big budget but you have to get that combination of situation and character exactly right.”

Smith immersed himself in another aspect of TV writing when he was part of a young team that the BBC World Service Trust sent to Phnom Penh to create Cambodia’s first ever soap opera. The drama, which translated means Taste of Life, was set in a small hospital and was to convey health messages to the public. But under the health umbrella, the team could write just about anything.

“The dilemmas were the same as in the British dramas, but the tracking was different. They were resolved much more slowly. In Cambodia, it might take 20 or 30 episodes before a couple even held hands,” said Smith.

“The dramas had to be filtered through that society. There were more stories about violence and revenge. We had stories about murders, superstitions, witchcraft and the country’s celebrities and powerful people. There were many acid attacks on women so we included that.

“The dramas had to be filtered through that society. There were more stories about violence and revenge. We had stories about murders, superstitions, witchcraft and the country’s celebrities and powerful people. There were many acid attacks on women so we included that.

“Western society tends to hide its violence. But there, poverty and violence were much closer to the surface.”

There also were censorship issues.

“People were always running around saying we can’t do this or can’t say that. Where we refused to buckle was anything with a health issue,” said Smith, who added that storylines on pregnant teenagers and abortion were acceptable.

What was not acceptable was a story about a gay character.

“We were told there were no gay people in Cambodia,” said Smith, who is openly gay. “We knew differently and wrote about it anyway.”

While in Cambodia, Smith used his free time to write. After he finished a script on spec for a British thriller, Smith was commissioned to write a film based on Jeff Noon’s short story, “Somewhere the Shadow,” about a serial killer who is “made safe,” and released back into society.

For research, Smith began reading about real-life serial killers and stumbled upon Russian Andrei Chikatilo, who was called the Ripper of Rostov. Chikatilo murdered and cannibalized at least 55 women and children during a 13-year period beginning in 1977.

“The idea that no one knew about this killer and the ignorance that went into denying his existence was amazing,” said Smith.

To make the most of the Russian setting, Smith moved a Chikatilo-like character back to the early ’50s.

“The investigation of a killer in the 1970s and 1980s was hampered by the residual effects of the brainwashing that happened earlier. [But] I thought, ‘Why not set it during that time when those pressures were most extreme?’ and that would have been during 1940s and ’50s.”

Child 44 and The Secret Speech are so vividly steeped in Russian culture that it feels as if Smith must have spend months in that country. Although Smith has visited Russia and Estonia, his research was based predominantly on textbooks, memoirs, and diaries. Smith’s interest was in the people and their daily routines. “I am not the person to minutely describe the buildings or the politics. I wanted to tell a story about these people and their world through their emotional struggles.”

Russia under Stalin existed under “a claustrophobia of prejudice,” he said. Anyone could find themselves arrested and tried for crimes against the state because of a misspoken word, an odd look, or an ongoing grudge. Those who were the least bit different, such as the mentally or physically handicapped, the homeless, Jews, gays, or foreigners were particularly targeted.

Russia under Stalin existed under “a claustrophobia of prejudice,” he said. Anyone could find themselves arrested and tried for crimes against the state because of a misspoken word, an odd look, or an ongoing grudge. Those who were the least bit different, such as the mentally or physically handicapped, the homeless, Jews, gays, or foreigners were particularly targeted.

“Often prejudice is spoken about as being detrimental to that person who is suffering that prejudice. But to me it is much more about how those prejudices are detrimental to the society as a whole.

“The most crystalline example was that real-life investigation [into Andrei Chikatilo] in which those same anti-societal rules were applied. It was assumed that only the mentally handicapped, or the homeless or whoever they didn’t like then could be guilty. Chikatilo had a party badge, he had a wife, so they simply thought he could not have been guilty. If they had done a semen or blood test on him, they would have caught him and perhaps more than 30 lives could have been saved.

“Those prejudices are extremely corrosive and destructive. The instinctive response should have been to stop this person. Instead, people were pursuing their own agendas. It is bizarre to think that something like prejudice could be prioritized above these horrific murders.”

Smith’s research on Russia uncovered situations, each more “appalling and shocking and absurd” than the last. For example, an orphanage might have 300 children, but only three spoons, he said.

Perhaps the oddest fact that Smith came across was when Stalin ordered a census. The census takers took precise accountings and came back with a population that was about 5 million lower than Stalin wanted.

“Mainly because Stalin had murdered so many,” Smith said. “His solution was to have the census takers executed and order a new census that did return the number he wanted. The ‘truth’ was wrong.

“This was the real world that people had to live in.”

Child 44 caused a bidding war among three publishers. It’s now printed in 22 countries. As publishers were vying for it, so were filmmakers. Ridley Scott bought the film rights.

“I’ve read the script and it’s great. But for me, any prediction is irrelevant. Until it gets made, it is temporary.”

But no initial stir has been quite like the controversy that erupted shortly after Smith was short-listed for the Booker Prize. Canongate publisher Jamie Byng took his tirade public when one of his titles, Helen Garner’s The Spare Room, was not nominated. Byng posted on the Booker website his “disgust” at the decision. Child 44, Byng said, is “a fairly well-written and well-paced thriller that is no more than that.... The idea that this novel could be determined to be a finer piece of fiction than The Spare Room is, I think, ludicrous.”

Smith finds the outrage by Byng, whom he has never met, “strange” and takes a higher road.

“I never thought being a champion of one book meant thumping on someone else’s. I never got into writing to get into this weird sparring. I’ve been told that [Byng] is a shrewd publisher and that he just wants to promote his author’s book.

“But any author’s success is great for the book industry. It brings in new readers. Success of one book helps another. That’s my personal take. It’s different than his.” Smith reportedly received a mid-six-figure advance for the first two novels and seven-figures for the US rights. He is, of course, pleased that his work commanded such a high price, but it has changed his life in only a few ways. Smith and his partner of four years, Ben Stephenson, who is controller of BBC drama commissioning, bought a condo in the trendy Jam Factory. From their apartment, the couple has a view of the London Eye and St. Paul’s Cathedral.

“But any author’s success is great for the book industry. It brings in new readers. Success of one book helps another. That’s my personal take. It’s different than his.” Smith reportedly received a mid-six-figure advance for the first two novels and seven-figures for the US rights. He is, of course, pleased that his work commanded such a high price, but it has changed his life in only a few ways. Smith and his partner of four years, Ben Stephenson, who is controller of BBC drama commissioning, bought a condo in the trendy Jam Factory. From their apartment, the couple has a view of the London Eye and St. Paul’s Cathedral.

When he is not writing, Smith is an avid fan of movies and TV series such as Lost, 24, Entourage, and “anything BBC makes.” He is a voracious reader. “There is nothing I wouldn’t read. I especially love Wilkie Collins and 19th century fiction, real page-turners with strong narratives. My bookshelf is quite eclectic.”

Smith is wrapping up the trilogy’s finale, which will be set in the 1960s through the 1980s. “The series will have shown the beginning and ending of Communist Russia. The regime is coming to an end,” said Smith. “Leo is older. It feels relevant to bring the trilogy to a close. There is a sense of melancholy and of crumbling.”

After that, Smith says he is “done with Russia.”

“There are a lot of other places I want to write about. I might do another historical or write scripts for the movies. I have loads of ideas I have not pitched yet. I just love telling stories.”

Child 44 has “opened up a lot of doors for me,” he said.

And if he continues to write novels, Smith expects the stories will be crime fiction.

“I love crime fiction because it is a wonderful way of telling stories. It is epic, it is domestic. Crime fiction tells everything about a society.”

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Summer Issue #110.