In crime pulps of the ’30s and ’40s there were also plenty of dicks who were actually janes, defiantly holding their own.

In crime pulps of the ’30s and ’40s there were also plenty of dicks who were actually janes, defiantly holding their own.

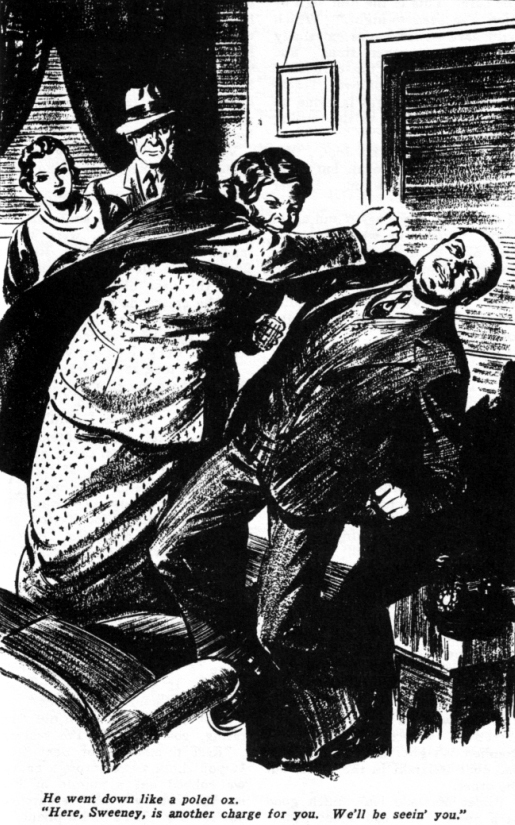

Cleve F. Adams’ foul-tempered Violet McDade is generally considered the first hardboiled woman detective. This illustration originally accompanied “Flowers for Violet” in Clues Detective Stories, May 1936.

Sometimes it’s hard to be a woman… especially when they’re also private detectives.

Oh, those poor gals. They seem to get it in the neck from both sides these days, misrepresented on the one hand by ivory tower feminists who overpraise characters like Kinsey Millhone, V.I. Warshawski, or Sharon McCone—for all the wrong reasons. They seem to believe these female gumshoes sprang out of nowhere, wholly formed, a mere 20 or so years ago, a revolutionary shot fired across the bow of some male chauvinist conspiracy.

On the other hand the same characters are sneered at and scorned by the knuckle-dragging traditionalists, with their trench-coat-and-fedora fetishes, who claim these detectives are actually about as hardboiled as afternoon tea, and that true hardboiled women never did and never will exist. I mean, come off it guys. What sort of slippery sliding scale of boiledness allows Lew “I just want to understand you” Archer to be classified as hardboiled, while V.I. “Take no prisoners” Warshawski is considered “softboiled”?

I’m not sure which group is more misguided or more in need of deflation, but they should both do a little more actual reading in the genre, and a little less huffing and puffing.

Truth is, the female eye goes back a hell of a lot further than Muller’s Edwin of the Iron Shoes—a fact that Muller herself has eagerly pointed out several times over the years.

The standard rhetoric goes that from the start of the P.I. genre, women were relegated solely to background characters or clumsy stereotypes—long-suffering secretaries (available in either plain and efficient or stacked and stupid), virginal victims, or drop-dead gorgeous femmes fatales (as though even a hint of sexuality, combined with just a drop of intelligence, was a sure sign that murder lurked in their hearts). This tunnel vision serves both camps nicely, for different reasons, but it conveniently sidesteps a few facts. Such as that the female characters created by Chandler, Hammett, and the better male writers of the genre were often just as well-developed, and their motives every bit as varied, as their male characters—they just weren’t always nice.

And, more importantly, it ignores the fact that in crime pulps of the ‘30s and ‘40s, although male detectives did indeed rule the roost, there were also plenty of dicks who were actually janes, defiantly holding their own. Each month, readers eagerly plopped down their dough to read the pulp escapades of these strong, tough, and, yes, even occasionally hardboiled janes.

One of the first, way back in 1933, was T.T. Flynn’s Trixie Meehan. Make no mistake—big, rugged Mike Harris of the Blaine Agency was supposedly the lead here, but his “pert sidekick,” a fellow op, was what made these occasionally screwball stories, which appeared in Detective Fiction Weekly, so special.

In the meantime, Grace Culver, created by Roswell Brown, was appearing regularly in The Shadow. Grace worked for the Noonan Detective Agency as a secretary and sometime-op, and while she wasn’t exactly hardboiled, she was certainly smart, brave, and independent. Cleve F. Adams’ nasty, foul-tempered Violet McDade is generally considered the first hardboiled lady eye. She and her long-suffering partner, Nevada Alvarado, slugged and bickered their way through a string of stories in the pulps.

Possessed of the charm and build of a NFL linebacker, D.B. McCandless’ Sarah Watson was another lovely piece of work. She didn’t have much patience for her young male assistant or for men in general—she gruffly admits she’d like to “beat up a man proper, for once,” and then proceeds to describe it in loving detail.

Then there’s Theodore Tinsley’s Carrie Cashin, certainly the most popular of the female pulp eyes. Attractive, smart, and determined as hell, she appeared in over three dozen pulp stories. Although she often posed as her male assistant’s secretary (Remington Steele, anyone?), there’s no doubt who the real boss was here.

And in a time when there were very few regular women writers in Black Mask, Katherine Brocklebank not only managed to sell them seven stories—she also created possibly Black Mask’s only female series character: Tex of the Border Service, who saw that justice was done along the Mexico/U.S. border.

Roswell Brown’s Grace Culver. A woman, a bad hair day, and a gun. Can you spell trouble? This illustration originally accompanied “Hit the Baby” in The Shadow Magazine, February 15, 1936.

Roswell Brown’s Grace Culver. A woman, a bad hair day, and a gun. Can you spell trouble? This illustration originally accompanied “Hit the Baby” in The Shadow Magazine, February 15, 1936.

Not that all the lady dicks were confined to short stories in the pulps. Rex Stout’s pistol-packin’ Dol Bonner showed up in the 1937 novel The Hand in the Glove, possibly the first book-length female shamus. Although there were no sequels, Dol later showed up in several of the Nero Wolfe tales.

Hot on Dol’s heels came Zelda Popkin’s Death Wears a White Gardenia (1938), which introduced Mary Carner, a smart and tough, crisply efficient detective who works at Blankfort's swanky, upscale Fifth Avenue store in New York, and would go on to appear in four more popular but now almost forgotten novels, making her—as far as I can tell—the first book-length series female private detective.

The next year, A.A. Fair (actually Erle Stanley Gardner) let loose Bertha Cool in The Bigger They Come, the first of what would become the longest series featuring a female gumshoe ever (and will still be, even when Grafton finally cranks out Z Is for Zero). Like Sarah Watson before her, Bertha Cool is one big, unpleasant chunk of detective, and nobody’s doormat. The books are an absolute treat, easily surpassing most of Gardner’s Perry Mason books for sheer entertainment.

And in 1947, skip tracer/P.I. Gale Gallagher appeared in I Found Him Dead, purportedly written by Gale herself (actually Will Oursler and Margaret Scott). It was followed a few years later by Chord in Crimson. Gallagher is arguably the missing link between the good girl amateur sleuths of the past and the tougher modern female P.I.s of the present. In the “tag end” of her twenties, she’s smart, well-dressed, and seems pretty self-assured and independent for that era. She goes to bars and jazz clubs alone, and enjoys the company of several men. She has a license to carry, though she rarely does, but she speaks with a dry wit and a casual toughness that is completely believable.

Some may sneer and declare these characters not “real” women because most were created by men, a sort of rebound-sexism. But that doesn’t subtract from the fact that these characters (and there were plenty of others) were all strong, tough and smart, and every bit as independent and as enjoyable to read about as their male contemporaries. Sometimes even more so.

And don’t get me started on the women who wrote for the hardboiled pulps....

SUGGESTED FURTHER READING

Hard-Boiled Dames: Stories Featuring Women Detectives, Reporters, Adventurers, and Criminals from the Pulp Fiction Magazines of the 1930s. Bernard Drew, ed., preface by Marcia Muller, St. Martin's Press, 1986.

Top of the Heap. Erle Stanley Gardner, Hard Case Crime, 2004. A Bertha Cool and Donald Lam mystery reprint.

Kevin Burton Smith is the founder and editor of The Thrilling Detective Web Site.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Spring Issue #89.