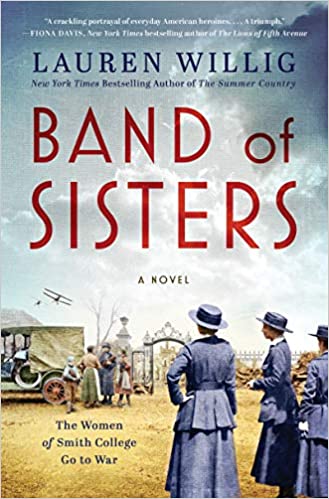

Lauren Willig, the beloved author of The Pink Carnation series, has turned her sights to the harrowing and inspiring relief efforts of a group of Smith College women stationed in France just a few short miles behind the front lines of WWI. They plunged into the effort to help, remaining in France through the end of the war and beyond. Willig shines a light on this largely unknown group of heroic women with her new novel, Band of Sisters.

Lauren Willig, the beloved author of The Pink Carnation series, has turned her sights to the harrowing and inspiring relief efforts of a group of Smith College women stationed in France just a few short miles behind the front lines of WWI. They plunged into the effort to help, remaining in France through the end of the war and beyond. Willig shines a light on this largely unknown group of heroic women with her new novel, Band of Sisters.

Robin Agnew for Mystery Scene: For readers who aren't sure what your book is about, can you explain a bit of the history behind Band of Sisters?

Lauren Willig: Band of Sisters is based on the true story of the Smith College Relief Unit, a group of enterprising Smith alumnae who charged off to France at the height of World War I to bring humanitarian aid to French villagers caught between two armies. We’ve all read about occupied France during World War II, but the Germans also occupied a chunk of France during World War I. In spring of 1917, the German lines were pushed back—not much, but a bit. Before they marched out, the Germans made sure to inflict maximum damage. They did everything from poisoning the wells to breaking the plows, systematically destroying anything that might provide either shelter or sustenance. They sent the able-bodied off to work camps in Germany—and then deliberately conducted the infirm, the elderly, the very young, back to their ruined villages in the hopes that they would die in droves and be a burden to the French war effort.

One Smith grad had other ideas. A groundbreaking archeologist (if you’re thinking Amelia Peabody, these women were absolutely sisters in spirit!) and occasional war nurse, Harriet Boyd Hawes heard of the crisis and returned the States to give a rousing speech at the Smith College Club in Boston, urging her compatriots to action. It was both the chance to alleviate considerable suffering—and to show the world just what the American college woman could do. Just three months later, Hawes set sail with the brand new all-female Smith College Relief Unit, which included two doctors, several social workers, a handful of kindergarten teachers, and “chauffeurs” (women who knew how to drive and would be in charge of their three trucks).

As you can imagine, it wasn’t all smooth sailing! Their headquarters, on the grounds of a ruined chateau, was a stone’s throw from the front. These urban, upper middle class women had considerable difficulties with livestock (including buying dozens of roosters when they meant to get hens!). There were differences of opinion and character that nearly scuppered the Unit before they could really get going. The British, who took over their sector, were deeply skeptical about women in their war zone. And, of course, the Germans did their best to shell them out of existence. But, despite all that, the women of the Smith College Relief Unit persevered in their mission—even when it came to facing down a German invasion. What they accomplished really has to be read to be believed!

You frame the chapters with letters home from the women. Are these all actual letters, or fictional letters, or a mixture?

All of the above! One of the best parts of writing Band of Sisters was getting to read the thousands of pages of letters the real members of the Smith College Relief Unit wrote home from the front. They were alternately snarky and earnest, making a joke out of all of their mishaps but deadly serious about the obligation they owed their villagers. I fell in love with them all—and I’ll confess that there were times I was tempted to ditch the whole novel, and just put together an annotated collection of their letters, because the letters were such joy to read and told the story so much better than I ever could.

My compromise with myself was the letters that you see at the start of each chapter. I wanted to give readers a taste of what those letters were like—and it also gave me a chance, with a large ensemble cast, to give you a window into the thoughts of characters we otherwise would only see through the eyes of our two heroines. The letters in the book are a pastiche of bits that are entirely my own invention, some pieces closely paraphrased from real letters, and a phrase or two taken wholesale from the letters that were published in the Smith Alumnae Quarterly at the time (sometimes over the objections of the letter writers, who wrote indignantly home telling their family members to stop sending their letters over to the alumnae mag).

For those who want to hear the real voices of the members of the Smith College Relief Unit (and you do! Trust me, you do!), I highly recommend heading over to the Smith Alumnae Quarterly website and clicking on the November 1917 through July 1918 editions in their electronic archives.

The work of historical fiction, it seems to me, is to extract a few characters that readers can bond with and create a compelling story for them....in this case, the background is so compelling, I can't imagine that was the hard part. How did you evolve your main characters, Emmie and Kate? And how were they based on real counterparts?

The work of historical fiction, it seems to me, is to extract a few characters that readers can bond with and create a compelling story for them....in this case, the background is so compelling, I can't imagine that was the hard part. How did you evolve your main characters, Emmie and Kate? And how were they based on real counterparts?

So true! Usually, I start with the characters and build my world around them. In this case, I was handed a world ready-made, down to the last detail. (Seriously, those letters. The details in them are incredible.) I had a story, but what I needed were characters to make it come alive. I didn’t want to use the lives of any of the real members of the unit for my two main characters. That seemed unfair to them, and a bit of a betrayal, to read their private letters and then air their innermost thoughts and feelings in public. But the sources I was reading did inspire my two fictional heroines, Kate and Emmie.

Kate is pure A Tree Grows in Brooklyn: she’s the daughter of Irish and Czech immigrants who won a scholarship to Smith at a time when anti-Catholic and anti-Irish sentiment was rife and the number of Catholics girls at Smith were in the single digits. In real life, one of the Unit’s two doctors, Maud Kelly, was Catholic—and I was very struck by the difference in tone when people referred to her. The other inspiration for Kate was the real assistant director of the Unit, Marie Wolfs, who was Belgian—and, while friendly with everyone and just as Smithie, always seemed a little apart from the rest of the Unit. What would it be like being part of the Unit but apart?

Kate’s college roommate Emmie is her opposite: Emmie is pure Mayflower and Knickerbocker, the daughter of a famous suffragette socialite. Emmie has the social connections Kate lacks but worries that she’ll never be able to live up to the example of her impressive mother—and that she’s not as talented as the other women. Emmie was inspired less by a specific woman in the group and more by broader social movements: I’d been reading up on both the “gilded socialites” of that older generation, the Gilded Age dowagers who threw their weight behind suffrage and women’s causes, and the Settlement House work of the younger generation, where the daughters of those socialites went into distressed urban areas and provided practical social service work. Many of the real members of the Unit had done Settlement House work, and I used their experiences and backgrounds to help create Emmie.

There are parts of the book that are set during shelling and follow the women as they retreat, as they were very near the front lines. How did you imagine that part of your book? It's pretty harrowing and feels so authentic.

I wish I could claim I imagined it! Here, again, I owe a debt to the real women of the Smith College Relief Unit, most of whom wrote home detailed accounts of their adventure. They were very aware that they’d been part of history and really felt the need to write it out: both to share it with the world, and, one imagines, to make sense for themselves of something that had been terrifying and fraught. Everything that happened on that retreat in the book—evacuating villages, setting up pop up food kitchens, members nearly being abandoned at a crossroads, being bombed out of Amiens—all of those are things that happened to the real women. In fact, the great frustration to me was that I couldn’t shoehorn in all the things that happened to them on that retreat, because there were even more.

In this present time of upheaval in our own world, I am finding reading wartime fiction almost soothing...I love reading about characters who have survived war and incredible situations and came out the other side. Did you find researching this book harrowing? Comforting? Soul changing?

I was about halfway through writing Band of Sisters when New York locked down last spring. And suddenly, what had been largely an academic exercise for me became something more—for the exact reasons you say. While the sirens were screaming past my window, I was writing about these Smithies getting the word that the Germans had broken through the line. While we got up at one a.m. to try to get a grocery delivery slot, I was writing about the Smith College Relief Unit parceling out food to refugees at railway stations. The weirdest bit was when I found myself, for several days in a row, writing about the exact same day: only a hundred and two years ago.

But they came out of it. That was what I reminded myself, as my two year old tugged me to the window, pointing the way to the park and asking me why we couldn’t go there, as my kindergartner wrestled with unfamiliar technologies that were suddenly school, the real school, three blocks away, blocked off as surely by disease as the Smithies were by the Germans. I took such comfort in knowing that they, too, had been lost and scared but had soldiered on and done the best they could, taking kindness as their guide.

There was one line from the real letters that jumped out at me, that I held onto through all the madness of the spring. After the harrowing experience of a German invasion, Elizabeth Bliss, class of 1908, wrote home, “It was marvelous to see how fine people are when all the external, superficial things are stripped away by a great emergency. I shall never forget all the beautiful as well as terrible things I saw."

I imagine we’ll remember the beautiful and the terrible as well—and how fine people are, when all the external, superficial things are stripped away.

As a novelist you had to give some shape to your story, so how did you create dramatic tension for your characters? One of the strongest parts of the book, for me, was the misunderstanding between Emmie and Kate. Though they so clearly love each other, they somehow can't get to the same place. How did you create drama and pacing for your story?

I spent 13 years at an all girls’ school, so I’ve always been fascinated by the ups and downs of female friendships, and particularly the ways those we love the most can also be the ones we understand least—and, how sometimes, our closest friends also reflect our deepest insecurities. Both Emmie and Kate see in the other something they lack: Kate envies Emmie her social connections, her comfort in the world, and feels that to Emmie’s people she’ll always be “just another Bridget: Irish, Catholic, and poor”, while Emmie envies Kate her academic success and her brilliant organizational skills.

The real events of 1917 and 1918 gave me the external frame for my story, and provided a certain amount of the pacing, but I knew the emotional heart of it needed to come from the relationship between my two main characters and their struggling through their preconceptions of each other to re-find their friendship. I think we’ve all had those friendships that are frozen at a certain moment in time—elementary school friends, college friends—where you have to grapple with the contrast between the people you were then and the people you’ve become now and try to see each other as you truly are—and discover whether the heart of the friendship is really something worth salvaging.

How long were the Smith women in France? Did they all leave after the war? Did they leave and come back? Did they maintain some kind of presence there, or was it over when the war ended?

The Smith College Relief Unit landed in France on August 14th, 1917—and although they were turfed out of their headquarters by the Germans in Operation Michael in March of 1918, they stayed and turned their hand to war work rather than relief work. As soon as it was safe, in January of 1919, the Unit went back to their headquarters at Grecourt and picked up where they left off—despite the extra havoc the Germans had wreaked in the interim! In 1920, the Unit officially handed off their work to the Secours d’Urgence, but even then, two members of the Unit stayed on, only departing when their library, civic center, and dispensary were transferred to the Bureau de Bienfaisance in 1922. So, five years after they first arrived, the last remnants of the Smith College Relief Unit said farewell to Grecourt.

But that’s not quite the end to the story: in 1924, the trustees of Smith College installed a replica of the Grecourt Gates at Smith, in token of the bravery of those women who went oversees to alleviate suffering in the midst of a war zone. It was a very moving reunion for the members of the Unit—and the gates are the iconic symbol of Smith College to this day.

I can't believe you aren't a Smith grad yourself. Smith must be delighted with this book, though. Do you have a relationship with Smith? Might you be speaking or teaching there in the future?

Although I’m not a Smithie, I like to think I’m of the lineage of Smith… in a kind of roundabout way. I spent my formative years at a little all girls’ school in New York ruled by a formidable Smith alumna, who came there straight out of Smith and was running the place within a decade—and continued to run it for the next thirty-odd years. Every year, our headmistress would call us together, and tell us again how getting a scholarship to Smith had transformed her life—and how much we owed the world in exchange for the education that had been given us. When I stumbled on the Smith College Relief Unit, when I read Harriet Boyd Hawes’ call to action, when I gobbled up the Unit members’ letters home, I could hear my headmistress’s voice in my head—and suddenly, so much about her and the values she attempted to drum into us made sense to me in a way they never had before. So, while I can’t claim a direct relationship with Smith, I’m terribly proud to have been shaped by an institution that was shaped by a Smithie.

Were you frustrated that the work of these women is so unknown? I'm so glad you've written about the great work they did. I had never heard about it and I wonder if you shared this frustration and it led to writing the book?

Frustrated does not even begin to describe it. The craziest thing is that the Smith College Relief Unit were a media sensation in their own day. Their founder, Harriet Boyd Hawes, very deliberately courted media attention, and the members of the unit were constantly complaining about being beset by reporters who tramped all the way out to their muddy headquarters at Grecourt. (Occasionally they set the reporters to work repairing chicken coops.) In fact, they were so well known that when they came under Red Cross control in 1918, their Red Cross handler joked that it was a huge publicity coup for the Red Cross, since everyone knew about the Smith Unit!

And now? Not even Smithies have heard about the Smith Unit. I’m ashamed to admit that when I first stumbled on Ruth Gaines’ memoir, Ladies of Grecourt, my first thought was that it had to be fiction—because what would a group of Smithies be doing in the Somme? I think it’s partly that shame that drove me to write the book. I was appalled at myself for not believing it might have happened. As an all girls’ school girl, you’d think I would know better!

The problem is that we’ve inherited a very limited narrative of World War I—or war generally, really. We think of it as a male province, as a matter of battles and tactics. If women come into it at all, they’re there as nurses. The truth is, as much as I would like to claim that the Smith Unit were wholly unique (and in some ways they were), there were a number of American women participating in relief work in the Somme, including heiresses Anne Morgan and Helen Clay Frick. In fact, the Smith Unit was so very successful and so very popular that it led to a Vassar Unit and a Wellesley Unit. But we’ve never heard of those either. I think part of the work of the historical novelist is reshaping our preconceptions of history and putting these forgotten narratives back in the story, because only that way do we get a full and accurate historical picture.

Finally, what are you working on next? As always, I look forward to where ever your interesting mind chooses to take your lucky readers.

Thank you! Right now, I’m working on a sort of prequel to Band of Sisters, currently entitled Smith II: the ReSmithening. As I was working on Band of Sisters, I became fascinated by the founder of the Smith College Relief Unit, Harriet Boyd Hawes: a brilliant, eccentric, divisive figure with a tangled past. After graduating Smith, she went off to the American School of Classical Studies in Athens in 1896, where she scandalized the locals by bicycling around the city in bloomers and scandalized her teachers by demanding to be allowed to excavate (women were expected to confine themselves to less energetic classical studies; it was suggested that Hawes become a librarian). Along the way, she was swept up in the Greco-Turkish War, and was decorated by the Queen of Greece for her nursing during the war.

And here’s where I really started to wonder…. Hawes is famous for excavating Crete. But, before returning to her studies, she hared off to the States to join the Red Cross and nurse in the Spanish-American War. Then she went off to Crete and made her name. What happened? Why the Spanish American War interlude? I couldn’t stop wondering about it, and as I wrote my own fictional version of Hawes, Betsy Hayes Rutherford, little hints about her past kept cropping up.

So that’s what I’m writing now! It’s the story of Betsy Hayes, a Smith grad who wants to be an archaeologist but whose life is changed forever by her experiences during the Greco-Turkish War and who redeems herself and discovers the woman she’s meant to be in the jungles of Cuba. It’s a coming of age story, a war story, and a story about what women can do. While researching this, I discovered some amazing—now forgotten!—stories about the heroic women who nursed with the Red Cross in Cuba and I’m so excited to bring their stories back to life in this book.

That book was originally slated to come out in March of 2022, but thanks to certain pandemic-driven childcare snafus, you’ll be seeing it in March of 2023 instead. (Please blame my 3- and 7-year-old for the delay, and direct all complaints to them.)

In my other writing life as one-third of “Team W,” Karen White, Beatriz Williams, and I are currently working on our fourth collaborative novel, a multi-generational saga set around a grand old mansion in Newport, Rhode Island, in the Gilded Age, the 1950s, and the present day. That one—still untitled—will be coming your way in autumn 2022.

Lauren Willig is a New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of historical fiction. Her works include The Other Daughter, The English Wife, The Forgotten Room (co-written with Karen White and Beatriz Williams), and the RITA Award winning Pink Carnation series. An alumna of Yale University, she has a graduate degree in history from Harvard and a J.D. from Harvard Law School. She is currently hard at work on her next book.