John Dickson Carr, Margery Allingham, and the Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

John Dickson Carr, Margery Allingham, and the Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

John Dickson Carr and Margery Allingham

In March 1949, John Dickson Carr was living in Mamaroneck, Connecticut. Margery Allingham, a friend from the Detection Club in London, was in the United States to publicize her latest book, More Work for the Undertaker. Carr presented Allingham and her husband, Philip (“Pip”) Youngman Carter, with a copy of his newly published The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and inscribed it as “Aunt Sally.”

I would like to approach the importance of this inscription somewhat obliquely. Nowadays, collectors often prefer to have only the author’s signature on their book, without any additional remarks—no note from the author about to whom the book is inscribed, no date, in fact no additional writing of any kind—only an autograph, usually on the title page beneath the author’s printed name, which is crossed out with a single line (only the gauche would use two lines thus making an X over the name). When I asked Colin Dexter to inscribe my copy of Last Seen Wearing, he told me that it was one of his early books and I therefore should prefer having only his signature. I insisted (successfully) that it be inscribed to me by name.

But it was not always thus. Frederic Dannay, in an early issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, described the variety of autographed books, and his article was reprinted in In the Queen’s Parlor by Ellery Queen (1957). Dannay said that a simple signature is the least interesting. Better is a signature and a message, but without a recipient. Then come inscribed copies with autograph, recipient, message, and date. Books in the third category vary in interest depending on the identity of the recipient and the significance of the message (it’s also more desirable to have the inscription dated near the publication date).

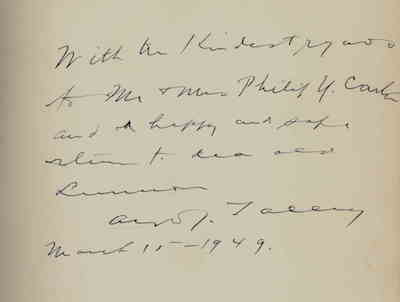

Margery Allingham's personal copy of The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Harper & Brothers, 1949) inscribed and presented to her and her husband by John Dickson Carr. (From the Mystery Scene library.)

Margery Allingham's personal copy of The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Harper & Brothers, 1949) inscribed and presented to her and her husband by John Dickson Carr. (From the Mystery Scene library.)

The best inscriptions tell a story—or hint at a story. When John Dickson Carr presented a copy of his second novel, The Lost Gallows, to his grandmother he included a note that it was in memory of times that he “told her better stories than this.” What stories? Carr didn’t say, but Carr fans have every right to speculate. To take another example, when Vincent Starrett inscribed a copy of The Unique Hamlet “To A. J. Morin after two glasses of cognac,” we can certainly wonder whether the cognac put Starrett in a generous mood, or if the gift was a planned part of a convivial evening. Starrett would write other intriguing inscriptions, for instance: “For Scott Cunningham some years after publication, and some hours before daylight.”

Sometimes authors present copies of their books to other writers, and often these inscriptions are the most interesting of all. I don’t know whether Carr met Pip Carter in the 1930s, when Carter was designing dust jackets. At least five of the British editions of Carr’s books have Carter dust jackets. But Carr certainly knew Carter’s wife Margery Allingham through The Detection Club in London. The club had been founded in 1930 by Anthony Berkeley and included luminaries as charter members—G.K. Chesterton, Agatha Christie, G.D. H. and M. Cole, Freeman Wills Crofts, R. Austin Freeman, John Rhode, Dorothy L. Sayers, and others. Margery Allingham became a member in 1934, and two years later Carr became the first American member (though living in England), and quickly was chosen as the Honorary Secretary.

Carr’s memories of the Detection Club and its members tended to be rather bibulous. He later wrote about “a somewhat drunken weekend with Margery and Pip Carter at their home in Essex,” and that may help explain why the inscription from Carr is not easy to read. After considerable help from my family, I interpret it (perhaps translate it would be more accurate) as:

“With the kindest regards to Mr & Mrs Philip Y. Carter and a happy and safe return to dear old London. Aunt Sally, March 15, 1949”

“With the kindest regards to Mr & Mrs Philip Y. Carter and a happy and safe return to dear old London. Aunt Sally, March 15, 1949”

(I have no doubt that I have misread several words...)

Which leads us back to the fascination of author inscriptions, especially when there is a hint of an untold story. Why did Carr call himself “Aunt Sally”? Aunt Sally was (and still remains in parts of England) a pub and fairground game—and readers who recall The Punch and Judy Murders know of Carr’s interest in fairground amusements. According to an 1866 account, “Aunt Sally is a big black doll on a stick, with a pipe in her mouth, and an orange or some toy for a prize, which you win by hitting her with a stick if you are lucky.” By extension an Aunt Sally is a person or object to throw at, to make a subject of ridicule or criticism, which is often unfair. Was there a joke of some sort between Carr and Allingham making him an Aunt Sally?

We shall probably never know—but always be intrigued.

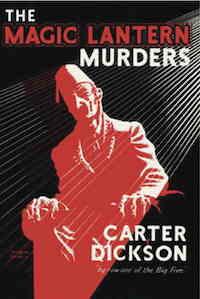

Two of the book jackets that Pip Carter designed for the Heinemann editions of John Dickson Carr’s “Carter Dickson” mysteries.

Two of the book jackets that Pip Carter designed for the Heinemann editions of John Dickson Carr’s “Carter Dickson” mysteries.

John Dickson Carr was chosen by the Doyle family to write the authorized biography of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and given unprecedented access to the author’s papers. Carr had worked with Adrian Conan Doyle, the youngest son of the famous author, on radio plays of the Professor Challenger stories. Adrian was delighted with the result, which was a best seller on both sides of the Atlantic. The two later collaborated on stories that were published in the 1952 collection The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes.

FURTHER READING

The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, by John Dickson Carr, Harper & Brothers, 1949

Artists in Crime: An Illustrated Survey of Crime Fiction First Edition Dust Wrappers 1920-1970, by John Cooper and B.A. Pike, Scolar Press (UK), 1995

John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles, by Douglas G. Greene, Otto Penzler Books, 1995

The Adventures of Margery Allingham, by Julia Jones, Golden Duck, 1999

Douglas G. Greene is the author of the award-winning biography John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles (1995). He is also the publisher of Crippen & Landru.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Winter Issue #128.