As slick and big-studio as it is, Gilda is noir to its rotten core.

As slick and big-studio as it is, Gilda is noir to its rotten core.

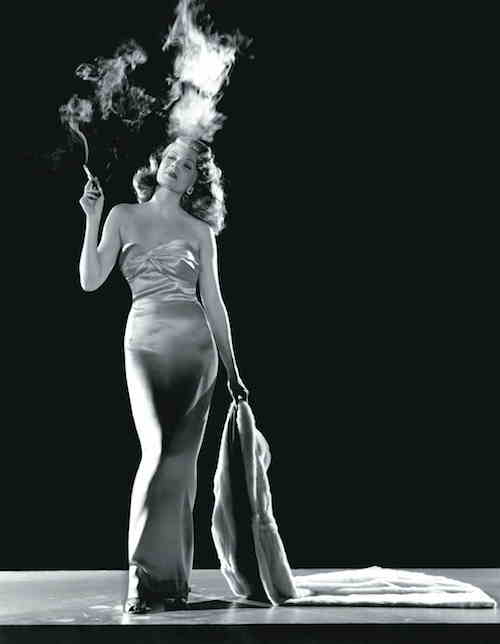

Rita Hayworth in Gilda (1946). Photo: Columbia Pictures.

Recently, I had the sublime experience of visiting the famous cine-paradise, the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York—a place I’d heard about for years and always wanted to visit. Invited up there by Jared Case, the Head of Cataloging and Access at its Motion Picture Department, I got a sneak peek at many of the facility’s wonders, including gorgeous Hollywood studio stills, posters, press books, and other archival items.

A distinct highlight was a glorious and haunting painted plaster mask made of Marlene Dietrich’s face, so delicate and exquisite I could barely look at it. I had always believed those cheek bones of hers were mostly Hurrell-lit fantasies. As it turns out, those planar majesties were God-given.

The occasion of my visit was to introduce a screening of Gilda (1946), and it became the first time I ever saw this film on a big screen—a gleaming print that swathed us in satiny black as if we were Gilda’s gloved fingers.

The story is simple. Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford), a ne’er-do-well gambler, hustles himself into a casino job and a fast friendship with the mysterious Ballin Mundson (George Mac ready). But everything changes when Ballin returns from a trip with his beautiful wife, Gilda (Rita Hayworth), with whom Johnny once shared a tumultuous romance that ended with the couple hating each other. Ballin charges Johnny with watching over Gilda, who resents both men’s obsessive and frequently cruel attempts to control her. The ensuing love triangle is, at turns, violent, tortured, and deeply romantic.

I first saw Gilda as a young girl, age nine or ten, on television, and I remember being enraptured. It seemed so glamorous—the glittering casino, the evening gowns and tuxedos, the exotic Buenos Aires locale. Beautiful Rita, handsome Glenn Ford, and their grand romance.

And, like everyone else I was transfixed during the famous scene of Gilda, in that iconic black dress, doing a gloved striptease to the lowdown tune, “Put the Blame on Mame.”

I remember watching her in that strapless dress, tight as a second skin, and wondering how she could keep it up—the aerodynamics of it—it signified to me the magical properties of womanhood.

I distinctly remember thinking, “This is what life is.”

In college, I saw the film again—and it was another a revelatory experience, but of a different kind.

I sat there, waiting for my childhood rapture—waiting to slip into the sumptuous, romantic story again. What unfurled instead was a dark, tortured world.

I realized that Gilda isn’t the center of the film at all, but is instead a glistening object. Much like the openly symbolic sword cane Ballin carries (which he calls “his little friend”), she is something to be passed between the two men, Ballin and Johnny, whose deepest feelings are, of course, for each other. I saw for the first time the dark, nihilistic thread (or zipper) through the satin center of the movie and it became even more fascinating, richer…. I felt like I had grown into it. It had showed me about adulthood, just not the adulthood I’d imagined.

Gilda presents a world of complexity, where feelings are never simple, every happy-ever-after has a price, and none of us completely know ourselves or what we’re capable of.

Love, in Gilda—or, perhaps more correctly, desire—is about power, powerlessness, control, and lack of control. We see this through the movie’s obsessive, self-conscious voyeurism—everyone seems to be watching each other, spying through windows and blinds, peering around corners, or through masks, but rarely ever touching.

The movie’s dark heart seems summed up in Johnny’s breathless voiceover, confessing, as he leaves Gilda, his old flame, with her husband Ballin, his new one:

It was all I could do to walk away. I wanted to go back up in that room and hit her. What scared me was, I-I wanted to hit him too. I wanted to go back and see them together with me not watching.

I wanted to know.

As slick and big-studio a film noir as it is, Gilda is noir to the rotten core. Because love here is a curse, a burden, and a weapon (cane, whip, glove). Love is about pain.

Love and hate, desire and contempt are not opposites at all but are in fact utterly inseparable. Or one and the same. As Ballin famously tells Gilda, “Hate can be a very exciting emotion ....There’s a heat in it that one can feel. Hate is the only thing that has ever warmed me.”

Ford and Hayworth in Gilda.

Ford and Hayworth in Gilda.

Photo: Columbia Pictures.

It’s chilling when Ballin says this. Later, when Hayworth’s Gilda echoes that line, in a desperate whisper, it may be the sexiest and saddest moment I’ve ever seen in film.

Watching Gilda a few weeks ago in preparation for the evening at Eastman House, a whole new shimmering layer peeked through.

Yes, I had an added appreciation for actors I’ve come to love, such as the delicious Joseph Calleia as the understanding cop, Obregon. But most of all I saw in Hayworth’s performance what I’d missed before, its pathos, her awareness that she matters less as a person than as a totem these two men wield to show their power, their loyalty, their complicated feelings towards each other.

Even the famous “Put the Blame on Mame” striptease scene now seems very different to me. Preceded by a musical number where she is precise, formal, ebullient, and quite feminine, in this number she is ballsy-burlesque, skittering raggedly by the end into something like desperation. Until it is that.

“Put the Blame on Mame” is, after all, a song about how a woman is to blame for the great Chicago Fire, the San Francisco earthquake, everything—just as Gilda’s beauty becomes the excuse for every act of depravity and control in the movie…she is a fantasy projection, not a real woman.

It’s all the more poignant given Hayworth’s tortured personal life, exploited by her father, her husbands, and Harry Cohn, head of Columbia. I hesitate even to quote the much-overquoted Hayworth line, reflecting on her own sad romantic history, “Men go to bed with Gilda, but they wake up with me.” Watching the film now, it seems clear that Gilda herself might say the same thing.

So in fact, I think now my nine-year-old self was getting a peek into the adult world, its beauty and its dark seams too.

Spoiler-alert: people, especially noir aficionados, always talk about the ending as being the one blemish on the movie; the fact that the production code demanded we learn that Gilda wasn’t the promiscuous adulteress that Johnny—and we—are led to believe.

But, “happy ending” aside (who, after having watched them tear at each other for 110 minutes, really believes these two will go onto a happy life together?), I love that Johnny is wrong. I love that we learn Gilda is innocent of the charges. Trapped between two men who cannot reckon with their own desires, she is the great beating heart of the movie. Guilty of nothing, of everything.

Megan Abbott is the Edgar Award-winning author of crime novels including Dare Me, The End of Everything, Bury Me Deep, Queenpin, The Song Is You, and Die a Little as well as a nonfiction book on hardboiled fiction and film noir.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Summer Issue #120.