That more and more mysteries are being published through more and more channels is both good news and bad news for the writer.

The good news: more ways to get published. The bad news: more ways to be lost in the shuffle. All four of these writers have achieved a measure of success but are less highly valued than they should be. Read on for a treasure trove of good writing!

Do mystery reviewers (male ones especially) have it in for the so-called cozy mystery, so much so that they have made the phrase itself a kind of slur? Not this reviewer. As a descriptive term, cozy is no more pejorative than hardboiled, and if I were forced to divide the whole of detective fiction into the toughs and the cozies, the classical figures I most revere (Queen, Christie, Carr, Marsh) would inevitably land in the cozy column. However, I do get impatient with the current crop of cozies when they are unconscionably padded and/or neglect the basic requirement of a good plot.

A self-described “skinny 5’11” redhead,” Carnegie (named for Andrew Carnegie because her father appreciated the public libraries he funded) was launched in Veiled Threats (2002), but I first made her acquaintance in Died to Match (2002), in which the nuptials are planned for an unusual venue: the Seattle Aquarium. Aside from the humorous narrative style, the inside details of wedding planning, and the fresh background, I was impressed by an element often absent from present-day cozies: real detection from fairly offered clues.

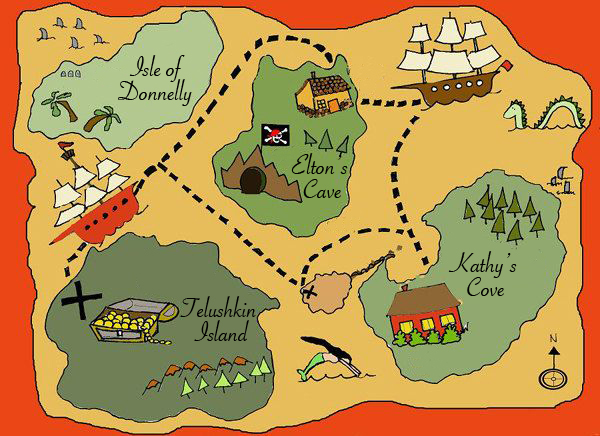

Cozy mystery heroines have all sorts of occupations—caterer, book dealer, tea-shop proprietor, domestic, animal breeder, journalist, landscape architect, teacher, librarian, ghostwriter, tour leader—but one of the most promising is that practiced by Deborah Donnelly’s Carnegie Kincaid: wedding planner. Weddings are as surefire a background for murder as for comedy or romance. The Kincaid series has won a following but, since paperbacks continue to get less review attention than hardcovers, it might have missed some of its potential audience.

Following May the Best Man Die (2003), Carnegie has her fourth case in Death Takes a Honeymoon (2005), in which she goes to the wedding of an old college friend as a reluctant guest but winds up running the show when the bride’s family can’t get along with the designated planner. Meanwhile, she becomes involved in investigating the recent death of her cousin, a firefighter, in an apparent smoke-jumping accident. The two plot elements come together in an exciting forest-fire climax. There’s no clued detection in this one, unless it was too subtle for me, but the plot is nicely involved and the humor on target. A couple of samples that could have come from Ron Goulart’s joke file: the bride, Tracy Kane, has become famous starring as a professional dog walker on a TV sitcom called Tails of the City, and the characters imbibe a local brew called Moose Drool Ale. (For all I know, that last may be authentic!) [Ed. note: It is.]

While Donnelly follows the dubious current practice of having a large cast of continuing characters—Carnegie’s journalist boyfriend, elderly business partner, obnoxious professional rival, Russian floral consultant—they are never dragged in for no reason or allowed to bring plot movement to a grinding halt so they can perform. The rocky romantic subplot is nicely integrated with the mystery. I’m less sanguine about Donnelly’s use of cliff-hanger endings, particularly annoying in the latest book since it’s so incongruous with the light overall tone. But the general quality of these novels disarms gripes.

BEN ELTON

BEN ELTON

If Mystery Scene were a British publication, calling Ben Elton an undervalued writer would be laughable. Though famed in the UK as stand-up comic, actor, playwright, and bestselling novelist, he has not gained the audience he deserves in the USA couple of his novels, including the Gold Dagger-winning Popcorn (1996), have found American publishers, but his most recent work is distributed here in its original British editions by Trafalgar Square. Elton has a satirist’s eye for contemporary lunacy, a fine novelist’s ability to create individual and involving characters, and a respect for the traditions of crime fiction.

Popcorn is a searing satire on contemporary society as viewed and influenced by its entertainment and information media. On the evening he wins an Oscar for his over-the-top violent Ordinary Americans, writer/director Bruce Delamitri (clearly inspired at least in his professional persona by Quentin Tarantino) is taken hostage by the notorious Mall Murderers who were inspired to their killing spree by his film. Along with the Oscar ceremony and general Hollywood hypocrisy (the cynical director’s acceptance speech is remarkable for its knee-jerk insincerity), Elton touches on racial politics, cosmetic surgery, rampant litigation, campus political correctness, television news and talk shows, commercials, and numerous other targets in service of his overarching theme: that everybody blames somebody else for everything and nobody takes responsibility for anything.

Elton’s later books continue to explore various crime/mystery subgenres while keeping a satirical focus. The stalker novel Blast From the Past (1997) is a riff on sexual politics, describing a rekindled romance between two extremists, a conservative American career Army officer and a left-wing British woman. Dead Famous (2001) targets a uniquely unsavory current phenomenon (the TV reality show), applies a contemporary frankness in language and sexual explicitness, and uses all this in service of an Agatha Christie-style closed circle whodunit as complexly and fairly plotted as a choice specimen from the Golden Age of Detection. High Society (2002), about an effort to legalize recreational drugs in Britain, shows that personalities more than serious argument determine political decision-making. Past Mortem (2004), a police procedural about an online reunion service and a serial killer of bullies, returns to fair-play detection and is entertaining as ever, but the murderer is too obvious too early.

What could be more welcome in the current market than a writer with a 21st century sensibility and range of references coupled with a classical command of mystery plotting?

In her series about Susanna, Lady Appleton, Elizabethan gentlewoman and herbalist, Kathy Lynn Emerson offers a remarkable range of vivid and telling details, whether domestic, scientific, political, social, legal, or religious. She also manages to create dialogue that achieves a period sound without being stilted or unnatural.

In her first appearance, Face Down in the Marrow-Bone Pie (1997), Susanna is living at Leigh Abbey in Kent, where she has a prickly but not completely unhappy relationship with her husband, Sir Robert, a serial philanderer. The steward at Appleton Manor has died suddenly while inappropriately dining on the elaborate concoction of the title, a delicacy usually enjoyed only by the very rich. Reports that he was frightened to death by the ghost of a young woman have scared off all the other servants. Against the wishes of Sir Robert, who has gone on a diplomatic mission to France, Susanna travels to Lancashire to clear up the mystery.

Like any heroine of a contemporary historical, Susanna is awfully independent and liberated for a woman of her time, but Emerson makes her attitudes and impulses believable. From the first book, the point is made that a widow’s position in Elizabethan society is far preferable to a wife’s, but Susanna doesn’t actually achieve widowhood until the fourth entry, Face Down Beneath the Eleanor Cross (2000), in which she is accused of bringing it on prematurely. Her trial in the Old Bailey for the murder of her husband is quite different from contemporary proceedings: the same jury are asked to bring verdicts on multiple felonies in a single day and are denied food and heat until they reach a decision.

The eighth novel, Face Down Below the Banqueting House (2005), describes the elaborate cooking facilities at Greenwich, the Maundy Thursday ceremony in which the Queen washes the feet of the poor (after three functionaries have washed them first), and the odd traveling arrangements which allow the Queen to commandeer any house that suits her and banish the inhabitants during her visit—unless they are of sufficiently elevated rank to be kept around. One of the houses selected for a royal visit is Susanna’s, and her exchange with the Queen’s self-important advance man is choice. A banqueting house, described as “a place where a considerable number of people could consume sweets and delicacies following the main part of their meal,” is built in a tree at Leigh Abbey in anticipation of the Queen’s visit, and from it a servant falls to his death. Accident, suicide, or murder?

Perseverance Press is one of the classiest of the regional publishers, producing a well-edited and beautifully packaged product. Still, when an established series becomes a victim of the find-me-a-blockbuster shakeout and moves from a New York publisher to a small specialty house, readers must wonder if this book is to be a bittersweet curtain call. But Emerson reports that another in the series is coming from Perseverance in 2006, and she also turned to a small publisher in launching a series about 1880s New York journalist Diana Spaulding with Deadlier Than the Pen (2004).

Ideally, historical mysteries should provide something on the real history, with a clear delineation of what is real and what imagined. Not until Face Down Beneath the Eleanor Cross did Emerson append a very brief historical note. Beginning with the sixth novel, Face Down Before Rebel Hooves (2001), Emerson has provided a character list with real people in the cast helpfully asterisked, and the notes have become more extensive. Face Down Across the Western Sea (2002), seventh in the series and last to be published by St. Martin’s, adds a map and a referral to her website for a full bibliography. The short story collection Murders and Other Confusions (2004) has a six-page introduction plus a concluding note to each story placing it in the context of the overall series.

Only one question remains: what if Lady Susanna finds a murder victim lying face up?

Like Ben Elton, Rabbi Joseph Telushkin has more on his mind than pure entertainment, and that may make his work problematic for some readers. If you’ve heard nationally syndicated radio talk show host Dennis Prager, a longtime friend and sometime nonfiction collaborator of Telushkin’s, you’ll recognize the very traditional religious and social views espoused on such issues as abortion, homosexuality, capital punishment, feminism, and the distinct roles of men and women in worship. Telushkin’s first novel even includes a reference to one of Prager’s favorite ethical conundrums: “If you saw your dog and a stranger, both drowning, and you could only save one, which one would you save?”

The Unorthodox Murder of Rabbi Wahl (1987) introduced Rabbi Daniel Winter, the second major rabbi detective in fiction, following Harry Kemelman’s David Small. Unorthodox was followed by two more, The Final Analysis of Dr. Stark (1988) and An Eye for an Eye (1991). While Kemelman’s purpose was to explain the tenets of Judaism to Jews and non-Jews alike, Telushkin has a broader agenda. Even those who least share Telushkin’s views will find him a skilled writer of fiction, whose prose and character building are fine and whose plotting (much rarer in the current market) recalls the clues-on-the-table puzzle spinning of the Golden Age formalists.

In his essay “Is This Any Job for a Nice Jewish Boy?” (in Synod of Sleuths, 1990), James Yaffe wrote disparagingly of Rabbi Winter’s first appearance, calling him less a character than “a collection of wish-fulfillment fantasies that belong to the vulgarest contemporary notions about success and glamor.” I believe Yaffe’s assessment is too harsh: Winter admits to too many human foibles and uncertainties to be charged with “intolerably smug superiority.” Even Yaffe admitted that Telushkin produced “an interesting puzzle, with good clues and a genuinely surprising solution that is also logical.”

The victim in the first novel is a female rabbi, murdered shortly after she appears on Winter’s radio program, seemingly patterned on Dennis Prager’s first Los Angeles program, “Religion on the Line.”

The Last Analysis of Dr. Stark, about the murder of a Los Angeles psychiatrist, is less impressive because of a problem similar to Ben Elton’s in Past Mortem: the main clue is just too obvious. An Eye for an Eye is perhaps the best of the three Winter novels, if also the one with the clearest agenda. When a man who killed his girlfriend gets off with a conviction for voluntary manslaughter, the victim’s incensed father kills the defendant and is released on bail as a result of Rabbi Winter’s arguments. But then the defense attorney is murdered, the father accused, and the rabbi faced with a crisis of conscience. As before, the puzzle spinning is expert, but in his eagerness to denounce the liberal courts, the author stacks the cards a little too neatly.

By contrast, Telushkin’s most recent novel, Heaven’s Witness (2004), written with Allen Estrin, gives full measure to all points of view in a novel with a theme of reincarnation, generally (to put it mildly) not a part of mainstream Christian or Jewish theology. The villain is a serial killer known as the Messenger, the amateur detective psychoanalyst-in-training Dr. Jordan Geller. With multiple suspects and expert mystery construction, the book struck me as one of the best of its year, and I hope Telushkin is back in the field to stay.

* * *

These four quite different writers represent scores of gifted practitioners, past and present, who have done better work than many bestselling authors. Read them to see if you agree with me, and then look for more of crime fiction’s hidden treasures.

This article first appeared in Mystery Scene Summer Issue #90.