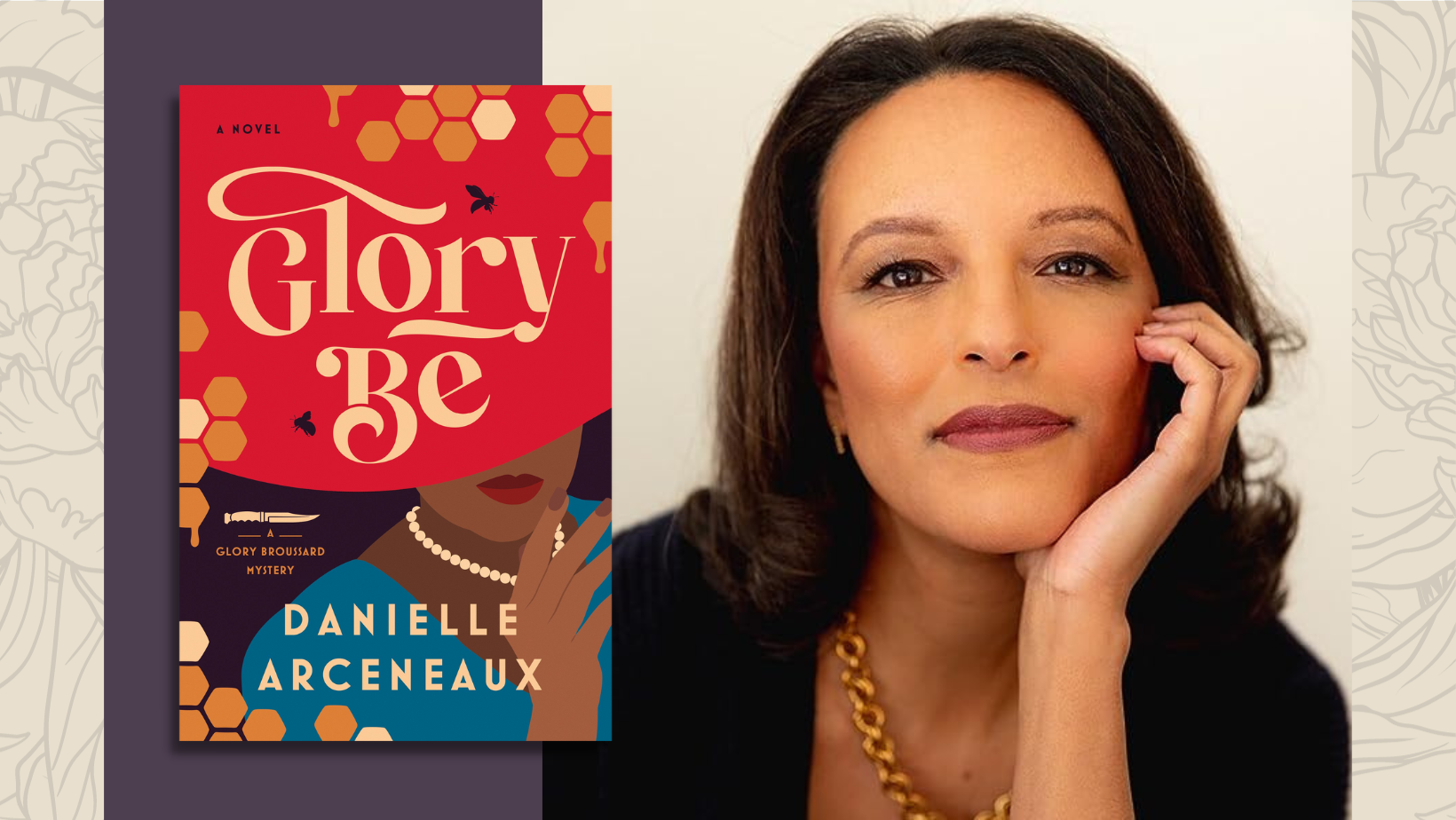

Danielle Arceneaux’s first novel, Glory Be, is a knockout. Glory Broussard is an older, heavier, African American woman living in Lafayette, Louisiana. She’s sometimes obnoxious, but also fearless and brave. She’s one of the more interesting and fully realized characters I’ve encountered in a long while. She’s not all good, she’s not all bad—in short, she’s human. By the end of her first adventure, you’ll be a little in love with her.

Arceneaux’s prose and storytelling seem far more sophisticated than the author's status as a communications strategist turned debut author might suggest. I loved everything about this book and was thrilled to speak with the author about her new series.

Robin Agnew for Mystery Scene: First of all, what is your own background? Did you, by chance, grow up in Louisiana where your novel is set?

Danielle Arceneaux: I am “of” Louisiana, but not technically from Louisiana. My parents and my large family are from in and around Lafayette, and still live there. As a young man, my father enlisted in the military and was stationed in Houston briefly, which was where I was born. When I was a couple years old we moved to a Marine Corps base in Twentynine Palms, California, and that’s where I was raised and lived until I went to college. Most people know this area as Joshua Tree.

In fact, when we moved off the base and into the town itself, we lived on one of the main roads into the Joshua Tree National Park campgrounds. It wasn’t even a national park when I grew up there in the '70s and '80s. It was a national monument, and growing up we called it The Monument. I’m saddened by how touristy it has become. All the real estate is getting snatched up and turned into Airbnbs, but growing up it was still extremely rural, isolated, and wild.

Just about every summer I’d spend weeks in Louisiana, running amok with my cousins. My grandparents were still sharecroppers in the 1980s, raising livestock and living in a house where we’d fetch well water and use an outhouse. The land is still untouched, and there’s a tree growing through the old house.

Just about every summer I’d spend weeks in Louisiana, running amok with my cousins. My grandparents were still sharecroppers in the 1980s, raising livestock and living in a house where we’d fetch well water and use an outhouse. The land is still untouched, and there’s a tree growing through the old house.

I grew up toggling between California and Louisiana, which really helps when writing about the South. I know Louisiana well, but I’m able to keep it at arm’s length. There are things that only exist in Louisiana that I’m still flabbergasted by, like the fact that drive-thru daiquiri establishments are real. The zoning, or lack thereof, always stands out to me when I visit. There are big expensive houses next to junkyards next to a nail salon. Readers will notice these things in Glory Be.

Are you a long time mystery fan, or did you just plunge in? Have you always wanted to write?

I’ve always loved mysteries, devouring Nancy Drew and Encyclopedia Brown as a kid. As an '80s kid there wasn’t a ton of supervision, so I always stayed up late watching shows like Cagney & Lacey, Remington Steele, Hill Street Blues, Murder, She Wrote, etc.

As a child, I announced to anyone who would listen that I wanted to be a writer, but didn’t get my butt properly in a chair until a few years ago. Better late than never, I suppose.

Looking at your website I see you are a longtime brand strategist. Your photo also shows you looking rather young and glamorous—kind of the opposite of Glory (though I see a resemblance to Glory’s daughter, Delphine)!

I’m probably not as young as you think; I am nearly 50! And as for glamorous, that’s kind! On the surface level, I understand why people might identify me with Delphine, Glory’s daughter. I live in Brooklyn and work with clients in public relations and marketing, which requires a certain level of polish, confidence and professionalism.

I have deep empathy for all the characters in Glory Be, but Glory, of course, is the main attraction. There aren’t a lot of women in pop culture who are older, complex, heavier and Black—and unapologetic about all of those things. Culturally we are hyper focused on younger people, but I’ve always enjoyed talking to older women. Someone once told me that the average book buyer is a woman in her 50s, yet we don’t see this represented from a main character perspective. It made me want to write something to and for this audience. I’m also keenly interested in how one ages with some measure of grace, bravery and openness. Glory is a good vessel to explore this because she has a great deal of courage, along with limitations and blind spots.

While there are many typically cozy elements in your novel, it’s not really what I would think of as a cozy, because of the harder edge of some of the circumstances (drugs and dog fighting for example) and the clear-eyed look you take at the racism in the South. What were you envisioning when you sat down to write?

I probably should have thought about this more when I sat down to write it! This conversation about genre has truly caught me by surprise. It’s not something I anticipated or thought through. I had a fun launch event at The Mysterious Bookshop in New York City and the booksellers told me it was their “unclassifiable” pick of the month. And some reviews on Goodreads have said that it’s not a typical cozy. Some readers love this, and others seem a little surprised.

I think it’s fair to say that it’s a traditional mystery or a cozy with an edge. Somewhere along the way, cozies became a very cliched genre, and I say this with zero snobbery whatsoever. People should read what they enjoy, but the American cozies can be a bit too saccharin in my view. British cozies have more punch. I hope books like Glory Be expand the genre.

With regards to the racism in the book, I was trying to depict the full experience of Glory's life, which has had some triumphs, but a lot of disappointments and racism. Glory’s race, along with her weight and age, makes her invisible and overlooked. These are important elements—not only do they shape her character and motivation, but being disregarded by others also happens to make her a great detective.

I thought it was great that Glory is a bookie—an occupation that I think of as old school, really. But you tie Glory into the community in interesting ways through her profession.

I liked the idea of Glory holding court somewhere on a regular basis, and her job as a bookie gives her a perch to interact with everyone in Lafayette, from the well-to-do to the fringes of society. I did some research into this when I started the book, and apparently the local bookie is still alive and well, even in this moment of online gambling and mass legalization of gambling across the country.

I also liked the novel's moral gray areas. Glory is many things, some of them obnoxious and unpleasant, but by the end of the novel, the reader has really come to love her and be on her side. You flesh out her character and made her so human. Can you talk about that a bit?

I had a lot of fun writing Glory and her characterization was pretty effortless. I have a theory that there are only two groups of people who are allowed to be grumpy and say inappropriate things without getting into too much trouble: children and women of a certain age. Glory has a lot of redeeming qualities, but as you said, she can also be narrow-minded, judgmental, and even petty. We all have parts of our personalities that are not pretty. Most of us have prejudices, inappropriate thoughts, intrusive thinking, jealousies, and resentments. With Glory, all of this is on naked display.

I recently caught Steel Magnolias on television and it occurred to me that Glory is a lot like Ouiser Boudreaux, the Shirley MacLaine character. Ouiser never stops complaining and has a very particular and distinctly Southern point-of-view about how people should behave. Yet as the movie goes on, you do see a softer side to her. You realize that her prickly exterior is more of a knee-jerk reaction to the changing world around her, as opposed to true malevolence. That’s how I think of Glory.

Also, she’s far older than you, I think—I was relating to her myself a good bit as I think I’m closer to her age. The scene where she talks about getting up for church hours early to get ready and get her creaky body moving felt so true! Did you rely on older relatives, perhaps?

Like I said earlier, I’m older than you probably realized! I’m certainly quite creaky in the morning and have issues with plantar fasciitis, so I know what it’s like to wake up with a limp from time to time. But yes, my mother is in her late 70s and it does take her quite a bit of time to get ready in the mornings. A lot of that comes from her.

Glory is full of bluster and confidence in public, and showing those aches and pains reveals a different side to her. Privately, she struggles more than she would ever let on to her acquaintances at church.

I also thought this was a subtle portrayal of grief. Maybe moving past grief doesn’t involve solving a murder, but Glory getting herself moving, and Delphine really looking around at the way her mother is living, all illustrate her grief. Was that a theme in your mind, or did it kind of develop as you wrote?

Yes, this was intentional and part of my quest to make her a complex and visceral character.

We live in a culture of self improvement. Grieving and depressed? Go to therapy, take the meds, and exercise! That’s great in theory, but in practice that’s much harder. Not everyone has access to psychotherapy or meds; and even if they do, there’s still a stigma around those things, especially within certain age groups and even more so within the Black community.

Grief can manifest itself in a lot of different ways, not just the stereotypical sadness that immediately comes to mind. In Glory’s case, her house has become unwieldy. Getting help requires a certain clarity and level of functioning. Delphine provides this clarity, even if it’s forced. And giving Glory a mission also helps.

I did not want to tie this up in too neat a bow. Glory is certainly better by the end of the book, but I think she will struggle with her losses for some time.

I thought the tone of the book, which covers some truly dark subjects, still had a lightness. How did you navigate that divide?

When I first shared it with my writer’s group, I was worried that people found Glory to be so funny. That wasn’t my intent at all, and I can’t write a joke to save my life. I came to realize that the humor comes from the fact that Glory sees the world through a very specific prism, and circumstances in the book force her to confront people and circumstances that she wants nothing to do with. That tension between Glory’s worldview, and the world as it actually is, drives the humor. I stopped worrying about it and let Glory take the wheel. It also lightens up the subject matter.

That said, I was concerned about her antics being interpreted as silly or slapstick. Delphine, her daughter, helps temper this. She is always there to reign in Glory’s worst instincts. And the darker elements you mentioned, mainly the violence that Glory encounters as part of her investigation, helps to keep the book a mystery and not overly comedic.

Are you thinking (I hope the answer is “Yes.”) that you’ve started a series? I think there is much more you can do with this fabulous character.

Yes, book two is in the works and is on track to be published next fall. Glory will have a whole new set of challenges to navigate!

Finally, can you talk about a book that was transformational for you as a reader or writer?

Alan Bradley’s Flavia de Luce series was a light bulb moment. I thought…here is a character that is funny and whip-smart and flawed, and yet totally lovable. And back to my theory that only children and women of certain age can get away with things…her being 11 really gives this character permission to do some pretty psychotic things with impunity! I’ve read them all, and I can barely remember a single murder or plotline, because Flavia is the star. A mystery writer needs a serviceable plot and murder, but a memorable character will always trump plot.

His books are probably cozier than mine (the English village, the vicar, etc.), but just below the surface the family is dealing with hard circumstances. The mother has died and the father has grown cold and detached. She and her siblings inhabit a falling down mansion in need of repair. Dodger, the household assistant, has trauma from the war and occasionally disappears into his PTSD.

This series was an eye opener for me. It was full of charm and humor, but also a real depth of emotion. When I read his books, I thought, “I’d like to write something like this one day.” I’ve heard rumblings that another installment is on the way, and I hope with all my heart that it’s true.

Danielle Arceneaux lives and works in Brooklyn, New York, and returns to Lafayette frequently.

Robin Agnew is a longtime Mystery Scene contributor and was the owner of Aunt Agatha's bookstore in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for 26 years. No longer a brick and mortar store, Aunt Agatha has an extensive used book collection is available at abebooks.com and the site auntagathas.com is home to more of Robin's writing.

Dick

Dick

Robin Agnew

Robin Agnew