"My hope as with all the Inspector Lu books is that it informs readers, as well as entertains them."

The third book in the Inspector Lu Fei series, The Magistrate, is about bad people doing bad things. Which, if you think about it, is an apt description of every other crime novel. But as with the first two books in the series, my goal in writing The Magistrate was to shed light on bad behavior that is intrinsically linked to its setting—China.

The plot of The Magistrate concerns a group of corrupt politicians who are being targeted by a shadowy figure who calls himself the Magistrate. Inspector Lu Fei gets involved when he comes to suspect his own investigation into the sex trafficking of young women from North Korea is somehow connected to this group of crooks and their anonymous tormentor.

Certainly, political corruption is not unique to China. But it seems like every other week another Chinese government official is on trial for taking bribes. By the Chinese Communist Party’s own accounting, more than one million officials have been punished for corruption since the country’s paramount leader, Xi Jinping, initiated an anti-corruption campaign a decade ago.

Imagine that—one million officials.

That number encompasses bureaucrats from the lowest levels of local government all the way up to members of the country’s top leadership. The Chinese have a pithy nickname for this wide-ranging group of scofflaws: “Tigers and Flies.”

Some might say corruption is baked into the clay of Chinese politics. In premodern times, local government was run by officials who were responsible for taxation, law enforcement, regional security, and maintaining social order. These officials were understaffed and underfunded and given their monopoly on power and their need to carry out their duties with limited resources, it was perhaps inevitable that corruption was widespread.

After the Communist Revolution, the government was reportedly very successful in reducing corruption (although that is up for debate). But following the market reforms in the late 1970s, officials (still grossly underpaid) seemed to take Deng Xiaoping at his word when he declared “to get rich is glorious.” And in the new go-go economy, there were lots of opportunities for under the table shenanigans—bribes for greasing bureaucratic wheels, property and land development deals, redistribution of state-owned assets—the list goes on.

And while Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign has stuck terror into the heart of many a dirty politician, critics say his goal is less about cleaning house—and more about getting rid of any potential rivals to power.

All of this is part of The Magistrate’s setting. But there is another, even more disturbing plotline, and that has to do with the sex trafficking of women who defect from North Korea, only to find themselves coerced into prostitution or forced marriage. These unfortunate girls and women really have nowhere to turn, because if they go to the Chinese authorities, they will be deported back to North Korea where chances are they will be sent to prison camps.

Of course, The Magistrate isn’t all doom and gloom. But my hope as with all the Inspector Lu books is that it informs readers, as well as entertains them.

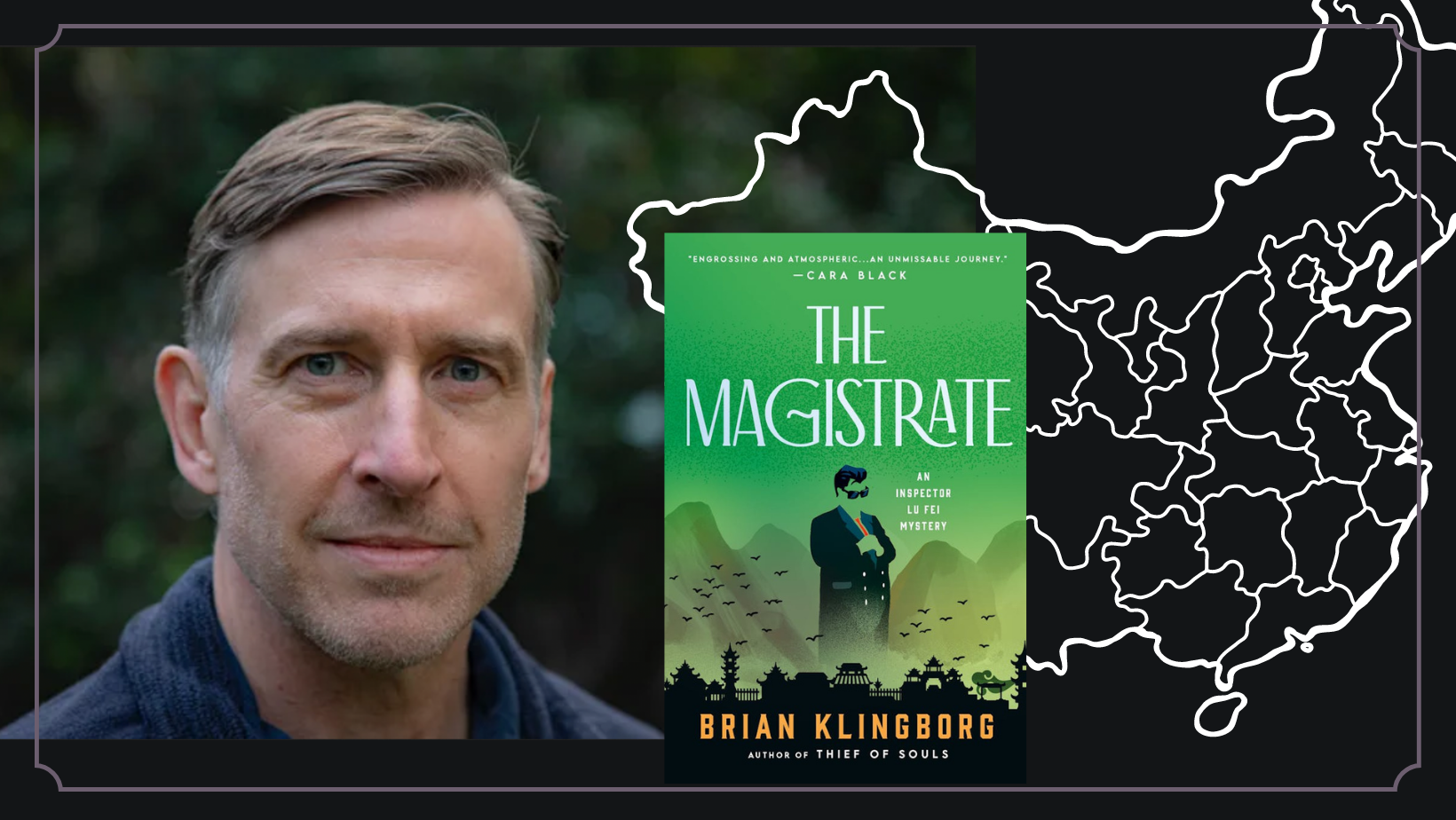

Brian Klingborg has both a B.A. (University of California, Davis) and an M.A. (Harvard) in East Asian Studies and spent years living and working in Asia. He currently works in early childhood educational publishing and lives in New York City. Klingborg is the author of two nonfiction books on Shaolin kung fu; Kill Devil Falls; and the Lu Fei China mystery series (Thief of Souls and Wild Prey.)