On his 85th birthday, Lawrence Block brings readers The Autobiography of Matthew Scudder, one hell of a weird-as-I-damn-well-please read.

Never can say goodbye... No, no, no… The Autobiography of Matthew Scudder, purportedly by Lawrence Block, published on the MWA Grandmaster’s 85th birthday, is something else. It’s a head spinner; a captivating memoir of Block’s most popular character. Purportedly written by Scudder himself.

It straddles the line between art and subject, between fiction and reality, between creator and art, between truth and lie, and our perceptions of them all.

“Look, I’m an old man,” says Matt (now more or less the same age as Block) “My mind’s like an old river, turning this way and that, and in no particular hurry to get where’s going.” At times Matt balks at details, and delves deeply into facets of his life he thought he’d forgotten. He moves back and forth in time.

But he keeps on writing.

He skips over major parts of his life, shrugging them off as inessential or already covered by Block, or just as something he didn’t feel like talking about. The Autobiography also serves as a sort of prequel to the series, mostly focused on the first 35 or so years of his life, figuring there’s already a “sufficient printed record” of the years since The Sins of the Fathers. It wanders along, enjoying a relaxed, late-night confessional vibe, not so much read as overheard.

Block has been urged over the years to write more about Matthew Scudder—maybe not to produce another novel, though he says, “I’m assured such would be welcome—but to furnish a biographical report on the man himself…”

But?

“The notion of writing about Scudder, of jotting down facts and observations about the fellow, has always rankled. I’ve turned surly when interviewers ask for a physical description, or seek out ways in which his personal history is or is not similar to mine,” Block says.

Trying to avoid the minefields of rankling or surliness, I asked Block how it went.

“Actually, It was both surprisingly easy and surprisingly difficult. The original suggestion, you’ll note, was that I write 4,000 words or so about Matthew Scudder. I knew I didn’t want to write four words, let alone 4,000, about the man, but I became more sanguine about it when I thought of shifting the assignment to the man himself.” Let Matt do it?

“Exactly. But when I actually sat down at my desk for The Autobiography of Matthew Scudder, I knew right away I’d need a lot more than 4,000 words to do what I wanted to do. And a day or two into it I knew I’d be writing at least 25K, and quite possibly a good deal more than that. It wound up around 65,000 words, which makes it novel length; indeed, it’s longer by a good margin than any of the first three books in the series.”

THE BEGINNING

I’ve been a huge fan of Block’s fictionalized adventures of New York City private eye Matthew Scudder almost from the moment back in my teens when I picked up a battered, tattered paperback of the series debut Sins of the Father at a rummage sale. The subsequent series, the tweaked and twisted tellings of Matt’s adventures, rendered in first person, have added up to a healthy chunk of Block’s professional career in the last 50 years.

I’ve been a huge fan of Block’s fictionalized adventures of New York City private eye Matthew Scudder almost from the moment back in my teens when I picked up a battered, tattered paperback of the series debut Sins of the Father at a rummage sale. The subsequent series, the tweaked and twisted tellings of Matt’s adventures, rendered in first person, have added up to a healthy chunk of Block’s professional career in the last 50 years.

In those early novels we were told Scudder’s fall-from-grace backstory: a husband, a father and a cop, one of New York's Finest. A decent-enough detective, honest enough to get by, although certainly no saint, and already a little too fond of the bottle. Until it all came crashing down, with Matt, off-duty and under the influence, trying to stop an armed holdup. A stray bullet in the ensuing shootout took the life of a little girl, and Matt soon found himself divorced and jobless.

Those early novels found him staggering through life in various stages of drunkenness, living in a Manhattan hotel and taking on the occasional job, doing "favors for friends," slowly drinking his way into the grave, amid increasingly frequent blackouts and less frequent half-ass attempts to “handle” his addiction.

Until the watershed moment of Shamus Award-winning Eight Million Ways to Die, the 1982 novel, the fifth in the series, in which Matt finally realizes—and admits—that he’s an alcoholic. And that was that. Five books, that even now, could stand as one of the all-time Great American Detective series.

Block told everyone who would listen that the Scudder series was toast, stick a fork in it, it’s done, until he brought him back in a 1984 short story "By the Dawn's Early Light," published in Playboy, which also nabbed a Shamus Award. Which was later expanded and adapted into the novel When the Sacred Ginmill Closes (1986). Since then the series has evolved, following Matt, now a recovering alcoholic, gradually coming to terms with his life. There are slips along the way, and mistakes, but he perseveres. In later books, he's become a licensed investigator, and even remarries (to Elaine, a former hooker who he first encountered in his days as a beat cop). There have been 12 more novels and numerous short stories and novellas since then, plus a graphic novel and a couple of feature films.

And then maybe eight or so years ago, Block told everyone he was stepping away from writing. Mind you, this is the same cheeky bugger who once published a writing guide entitled Telling Lies for Fun & Profit.

And then maybe eight or so years ago, Block told everyone he was stepping away from writing. Mind you, this is the same cheeky bugger who once published a writing guide entitled Telling Lies for Fun & Profit.

So really, how far can we trust him?

Since his “stepping away,” he’s become a one-man publishing industry, slowly rereleasing his back catalog. He’s edited several anthologies, and written a novella, A Time to Scatter Stones, that seemed like a final, unexpectedly sensual farewell to Matt and Elaine. He also put out Dead Girl Blues (2020), a standalone crime novel, and The Burglar Who Met Fredric Brown (2022), an oddball (possible) goodbye to another of Block’s popular characters, amateur sleuth/bookstore owner/gentleman thief Bernie Rhodenbarr.

THE WEIRD MIDDLE

And now this, a novel written purportedly in Matt’s own voice, the PI turned a reluctant chronicler of his own (fictional) life, scribbling away, not even sure why. Block (as Matt) seems assured and focused in the series; yet Matt is tentative here, more casual, resentful, and mildly peeved at times, dismissive of Block’s embellishments in his “slightly fictionalized” rendition of Matt’s “real-life” adventures.

And yet, as is his wont, Matt has allowed Block to put his name on the cover. Without any indication Matt himself has profited from any of it.

Whatever.

Still, it’s a delight to hear Matt doing the talking, for once. This is a book without any big drama or reveals (and what there is, is mostly downplayed) beyond one man’s life and times, the things that happened to him, a few random thoughts and reminisces about family, friends, etc. And yet I found it all compelling and even fascinating. There are no serial killers, psychotic murderers, Big Apple whack jobs, or any of Block’s stock-in-trade, except in passing. Those were already covered in the books.

Matt complains at times, “It’s a slog, remembering all of this, writing it down,” and even wonders, “Is anybody going to want to read all this?”

I wanted to reassure him that, “Yes, we do,” but characteristically, he was unavailable to interview. The man, after all, does value his privacy.

So I had to settle for Block. We swapped a few emails. I apologized for the smoke from all those Canadian wildfires that had rendered New York City’s air almost unbreathable, and then stealing a line from a million Amazon reviews, I assured Block that the pages practically turned themselves. How did the writing go?

“Well, writing’s a different process for me than it used to be. An hour or two at my desk and I’m done. When I'm on a book, it's generally a matter of sitting at my desk after (or instead of) breakfast and working for a few hours. Aging happens, and affects everything, writing included. I'm less inclined these days to start anything, less committed to finishing it, and able to put in fewer hours at a stretch. It can still go well, and often does, but not always. I used to go away to write, more often than not. I'd hole up in a writers colony or take a hotel room and focus entirely on writing. I haven't done that in some years now, and can't imagine wanting to. I'd rather stay home.

“At the risk of appearing precious or disingenuous,” continued Block, “I might say that writing the book was for me very much as it was for Matthew—letting the narrative go where it wanted, sometimes deleting a day’s work at the day’s end, having material in the book occur in my imagination like a long-forgotten memory surfacing in Matthew’s consciousness. In this respect, I was more interested and involved in the writing of this book than anything I can recall.

“I don’t think there was ever a moment during the several months I spent when I questioned the value of what I was doing,” he added. “I knew it was the book I wanted to be writing. I also knew it was one I’d want to self-publish; that’s been true of virtually everything I’ve done in recent years, but it seemed particularly clear here, because the likely audience for it would be small.” I was surprised. “Small?”

“Well, I couldn’t imagine anyone wanting to read it, or being able to read it with enjoyment, who wasn’t already a fairly committed fan of the series.” I pleaded guilty,, assuring him I was fairly committed. Or should be.

“Even then, I couldn’t take reader enthusiasm for granted; someone who read the books just for the stories, or in the hope that TJ would say something amusing—well, why would he give a rat’s ass about Matt’s disappointment at being unable to take third-year Latin?”

Uh, guilty. Girding my loins, I asked him if he was pleased with the end result?

“Yes. Very pleased,” he admitted. “Exhilarated, really. Lynne (Block’s wife) is my first reader, and she gave me the perfect compliment. She said she had to keep reminding herself that what she was reading was fiction.”

That’s what I was getting at. I asked Block if he sometimes found himself unsure whose life exactly he was putting down? Or going back over the previous books? Obviously, there are always overlaps between a writer and his subject—otherwise anyone could write anything—but did he find himself cannibalizing parts of other people’s lives (not just his) or scraps of his own fiction for Scudder’s?

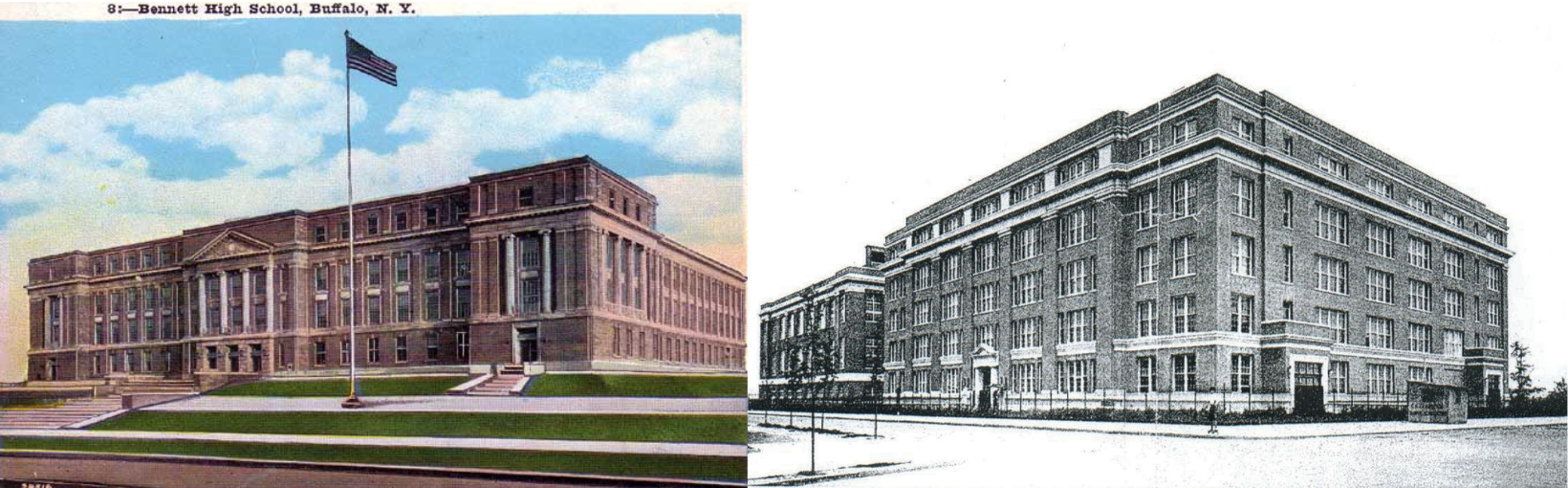

“The question’s a good one,” he admitted. “I knew going in that the last thing I wanted to do was go back to the books, or repeat material I’d already covered. I wanted to cover material I hadn’t previously addressed, and to do that I had to invent. All Matthew’s family background, all the material on his early years, just came to me as I wrote it. I hadn’t given it much thought before, I’d never known anything about his first wife’s background or how he wound up at the police academy or, well, much of anything. There’s nothing in my own personal history that corresponds to his. Our families were nothing alike, our ethnic backgrounds, our childhoods—entirely different. The closest we come to overlapping is that I did read Cicero in third-year Latin, at Louis J. Bennett High School in Buffalo, [New York,] an opportunity that was denied to Matthew at James Monroe High in the Bronx. My teacher was Miss Daly, not Miss Rudin, and some 25 years earlier she had been my mother’s Latin teacher.”

(Right) Louis J. Bennett High School in Buffalo, New York, the site of Lawrence Block's third-year Latin studies with Miss Daly and (left) James Monroe High School in the Bronx, the teenage stomping grounds of young Matthew Scudder.

THE END — OR IS IT?

And so it goes, as Matt recounts his life, right up to the present, offering a glimpse of his and Elaine’s life, their friends…. Matt’s still attending meetings and they see Mick and his wife frequently. Life goes on, as it does for Block himself.

“Regrets. Yes, of course. There are things I could have done better,” Matt confesses at the book’s conclusion. “But no bitter regrets, not really, because I truly like where I am. And the trip that got me here has had its moments.”

I found it just so unexpectedly moving, and I told Block so.

“Thanks,” he said, and threw me a zinger that still has my head spinning. “One way to look at the book—and to all books, really—that might be interesting. The book immediately preceding this one,The Burglar Who Met Fredric Brown, posits a parallel universe (a multiverse for you kiddies out there) into which Bernie and his friend Carolyn are catapulted, a world in which the two banes of Bernie’s existence, online bookselling and security cameras, do not exist. I hit on this because it was the only way I could imagine Bernie’s continuing existence as a burglar and bookseller, and it solved that problem while presenting others, but all in all it worked well for me—and for Bernie.

“I mention this because since then—and perhaps before it as well—I’ve realized that every work of fiction takes place in a parallel world, specifically a world in which everything implied or recounted in The Autobiography is true… everything Matt tells us is literally true—or at least as true as his own memory and perceptions can make it.

“In our world, of course, all of this is a work of the imagination, and specifically of my imagination. A reader can so regard it, or—to the extent that I’ve done my job effectively—he/she can enter into the book’s universe.

“Now you and I, Kevin, are in this world, although we’ve both spent time in the book’s world. But this world is the real one, right?

“Well, we’d have to think so, wouldn’t we?”

Weird, right?

A Lawrence Block Matthew Scudder Reading List

The Sins of the Fathers (1976)

Time to Murder and Create (1979)

In the Midst of Death (1976)

A Stab in the Dark (1981)

Eight Million Ways to Die (1982)

When the Sacred Ginmill Closes (1986)

Out on the Cutting Edge (1989)

A Ticket to the Boneyard (1990)

A Dance at the Slaughterhouse (1991)

A Walk Among the Tombstones (1992)

The Devil Knows You're Dead (1993)

A Long Line of Dead Men (1994)

Even the Wicked (1996)

Everybody Dies (1998)

Hope to Die (2001)

All the Flowers Are Dying (2005)

A Drop of the Hard Stuff (2011)

The Night and The Music (2013)

Other books

The Autobiography of Matthew Scudder (2023)

Omnibus editions

The Matt Scudder Mysteries (1997)

The Matt Scudder Mysteries Vol 2 (1997)

Kevin Burton Smith is a Montreal editor, author, critic, essayist, would-be cartoonist, blogger and Twittist currently stationed in the peculiar state-of-mind known as Southern California. His often rather dubious but always enthusiastic writings on crime fiction, music, film, bicycling, and sundry other topics have appeared in web and print publications all over the world, including Mystery Scene, Crimespree, The Rap Sheet, January Magazine, Details, Blue Murder, The Mystery Readers Journal, Word Wrights, Over My Dead Body, Crime Time (Britain), Crime Factory (Australia) and Musica Jazz (Italy). He is also the founder/editor of the award-winning Thrilling Detective Web Site, the internet's (erm...) premier resource for fans of fictional private eyes and other tough guys and gals in literature, film, radio, television and other media.