My family moved around a lot when I was young, but the one constant was that once a week my mother would bundle me and my brother into the car and head to the main library branch of whatever town we were living in. My brother would race to the section on trains, and I’d wander over to Nancy Drew and Agatha Christie. We’d grab as many books as allowed and then wait for my mother to check them out.

I loved the snap of the Mylar covering as the book was opened, followed by the satisfying “chunk” of the mechanical stamp coming down hard on the due date card. Library books protected me, wrapping me in the safe bubble of other stories when I was nervous about attending a new school or making new friends. There were other worlds out there, each novel reminded me. Worlds where I might fit in.

At the time, I couldn’t imagine anything better than being a librarian. To have all of those books to peruse at my pleasure, what an embarrassment of reading riches. Later, while researching a novel, I stumbled upon the existence of the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library, which holds literary archives, manuscripts, and printed books of over 400 authors like Vladimir Nabokov, Mark Twain, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The treasures in the Berg Collection offer a window into the creative process. The scratched-out words in a draft of a Walt Whitman poem, for example, or Virginia Woolf’s entries in her diary, remind us that these authors who we revere were human, and that the act of writing is a difficult one, and shouldn’t come easy.

The value of such collections can’t be understated.

After a thief was caught stealing $1.8 million in rare books and manuscripts from Columbia University’s Butler Library in the 1990s, Jean Ashton, the library’s director of rare books and manuscripts, went before the judge and requested a harsher sentence. She explained that the items were worth more than their stated value because they were important pieces of history and culture, and that their loss would have a dramatic impact on scholarly research. The judge was duly impressed, and remanded a longer sentence. Later, a law was passed protecting cultural heritage resources, so that from that point forward, thefts from a museum or library were taken more seriously.

To read a draft of a Walt Whitman poem is an honor and a privilege, one that Ms. Ashton protected. As a child, I looked up to librarians as literary heroes, and that remains true to this day.

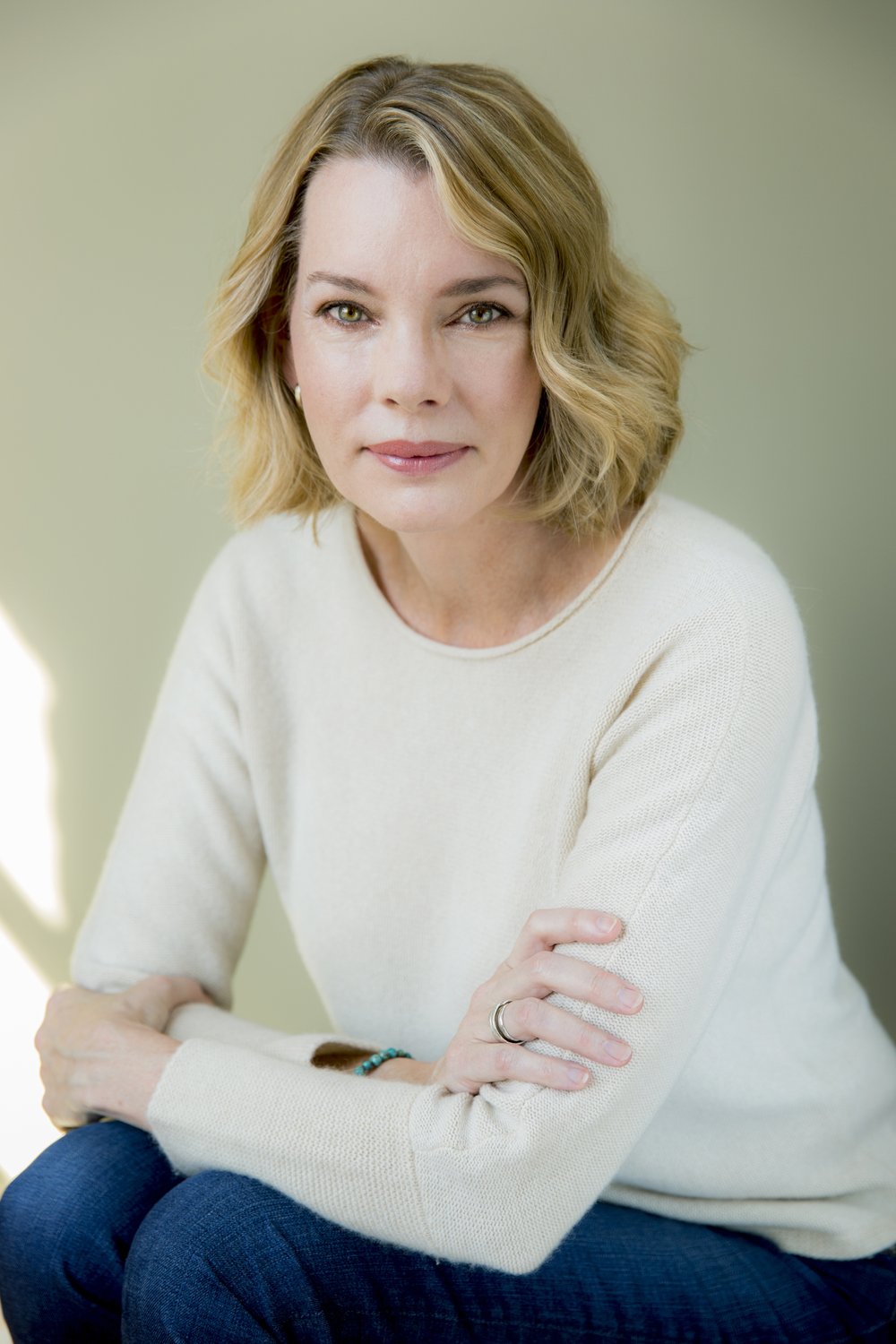

Fiona Davis began her career in New York City as an actress, but after getting a master's degree at Columbia Journalism School, she fell in love with writing, eventually settling down as an author of historical fiction. Fiona's books, which included The Lions of Fifth Avenue, Chelsea Girls, and The Masterpiece among others, have been translated into more than a dozen languages. She's a graduate of the College of William & Mary and is based in New York City.

This “Writers on Reading” essay was originally published in “At the Scene” enews August 2020 as a first-look exclusive to our enewsletter subscribers.