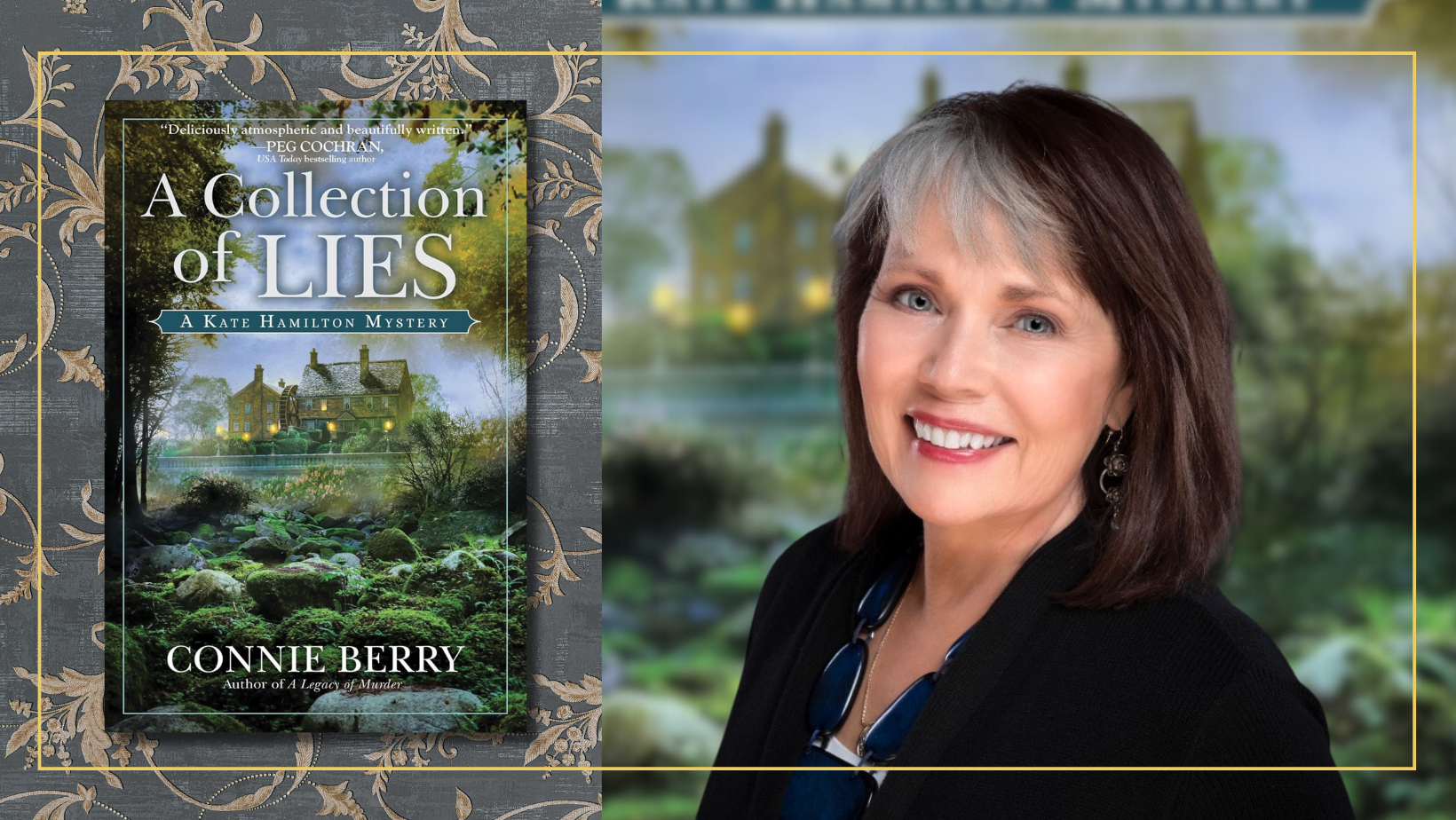

Connie Berry’s Kate Hamilton books feature an American antiques dealer who has family ties overseas through her Scottish husband. As the series opens, Kate, recently widowed, is visiting her sister-in-law, Eleanor, on the Isle of Glenroth. Kate hopes that she can make peace with the prickly Eleanor, who blames Kate for her brother's drowning. There on the island, she quickly encounters a murder mystery and meets an English man, a detective, naturally, who will change her life.

Berry’s books are a wonderful combination of tricky plots, rich characters, and beautiful settings, and for anyone who adores a British village mystery, this is the series for you. Each novel focuses on a story in the past, often highlighting some specific antique element. In A Collection of Lies, the fifth in the series, that element is lacemaking and fabric restoration.

Robin Agnew for Mystery Scene: I am so sorry I haven’t discovered this series sooner! I can’t wait to catch up. I did notice, looking at your publication history, that your first book came out during the COVID pandemic. Was that a challenge to promote?

Connie Berry: Actually, my first two books, A Dream of Death and A Legacy of Murder, were both published in 2019, before COVID. I remember feeling sorry for new authors whose big debut happened during those terrible, isolating months—no launch parties, no bookstore signings or library talks, no conferences. It’s hard enough getting your name out there when you’re new, but to do everything online must have been extremely discouraging—and daunting. We were just learning how to use Zoom.

However, having two books out in the same year was a challenge as well. Looking back, I wish I’d lobbied for bringing them out in 2019 and 2020, respectively, because Legacy got overshadowed. A debut novel always gets more attention, and in terms of awards, I was actually competing against myself. But it is what it is—and I’m glad both are out there in the world.

I really love when an amateur sleuth uses their professional expertise to solve a crime, as is the case here. Kate’s expertise lies in antiques, and I understand yours does as well. Can you talk about the relationship between your own expertise and Kate’s?

You’re right—Kate and I share a similar background, as both our parents were antiques collectors and dealers. Strange coincidence, right? New writers are often told to “Write what you know.” That’s not always sound advice, of course. Crime writers (thankfully) don’t have to be criminals, and writers often write about worlds we wish we knew. But in my case, I did know the world of antiques. My parents began collecting almost as soon as they were married, and when the collection threatened to overwhelm our house, they opened a shop. From childhood, I attended auctions and shows. Every vacation was a thinly disguised buying trip. During high school, I worked in the shop on weekends.

Kate, unlike me, had her own shop in Jackson Falls, Ohio. Now that she’s living in the UK, she works with Ivor Tweedy at The Cabinet of Curiosities, an antiques and antiquities business in the fictional Suffolk village of Long Barston. Kate’s professional expertise has proven helpful to the police several times. While this isn’t true of me, I draw upon memories of stories I heard growing up (antiques dealers are a gossipy lot) and of my mother, who was a brilliant researcher. She documented as much of the history of an object as she could uncover and shared that information with buyers. “That way,” she said, “people aren’t just buying an object; they’re buying a piece of history.”

You describe Kate as a “divvy.” Can you explain where that term came from? Is it a real thing? Do you know any divvys?

Used in the context of antiques, the word divvy (“diviner”) refers to someone who has a near-supernatural ability to detect a valuable object when others can’t—and to tell the real thing from a fake, like Lovejoy in the wonderful old British TV series.

Kate’s father, who taught her about antiques, called her a divvy, an antiques whisperer, able to spot the single treasure in a houseful of junk—although Kate is quick to point out that it isn’t always true. What is true, is the fact that Kate experiences certain physical sensations in the presence of an object of great age and beauty—flushed skin, dry mouth, racing heart. And sometimes a word or a phrase forms in her mind—sadness, joy, fear, jealousy, danger—as if the emotional atmosphere in which an object once existed had seeped into the cracks and crevices along with the dust and grime. Kate, who doesn’t believe in the supernatural, chalks this up to her notoriously overactive imagination. She’s never told a soul (even her new husband) because she doesn’t understand it herself.

Where did this come from? I had a similar but far less dramatic experience as a child. My parents had been to central America where a woman on the street offered to sell them a hand-carved wooden doll, folk art. Begged them, actually. The problem was they immediately saw that the doll had belonged to a small child, who was watching from a doorway. Not knowing what to do, they decided the family must have badly needed the money, and that if they didn’t buy the doll, the woman would just sell it to someone else who might take advantage of them. So they bought the doll and paid the woman three times what she’d asked. Nevertheless, it bothered them, and they left, not knowing if they’d done the right thing or not. Hearing the story later, I held the doll in my hands and felt a tremendous sense of sadness and loss—what I imagined the little child had felt. I still have the doll and often think of the little girl who had to give it up for the sake of her family. I use this experience and others in the Kate books.

I was fascinated by the character of Gideon. How did you come up with the idea for him to live as closely as possible to a Victorian gentleman?

The best stories, in my opinion, are true—or at least partly true. As a lover of history, I’ve always been fascinated by the possibility of breaching the wall separating past and present. Years ago, I loved the BBC documentaries in which people volunteered to live for a time exactly as people did in the past (Living in the Past, Turn Back Time). Much later, I read about a young man in the UK who lives and dresses as a Regency gentleman. To make a living, he designs and sews reproduction Regency men’s clothing. Turns out he isn’t the only one. Another man recreates the life of a Victorian gentleman, and a married couple in the UK live as they would have in the 1930s. This time-travel angle really fascinates me, and I wanted to explore the reasons why someone would actually attempt it. Plus, Gideon has his own past to deal with, so his lifestyle becomes almost a metaphor.

The relationship between Tom and Kate grounds the book. I see looking back you may have been slowly drawing them together through the novels. When you began the series, did you have an arc in mind for the characters, and what’s next for them?

I’m glad you like Tom and Kate. I do, too, and have enjoyed writing about their developing relationship. They didn’t start out on the best of footings, and Kate’s interest in Tom develops despite her determination never to marry again. Losing her first husband suddenly and unexpectedly was a trauma causing something like PTSD. And the relationship between Tom and Kate has been fraught with problems. They have two careers, two families, two sets of friends, two lives separated by an ocean.

In A Dream of Death, Kate reflects on the irony that of all the men her friends have tried to set her up with since her husband’s death, Tom, an English policeman, is the only one she’s ever really felt an attraction for. They’ve had to deal with obstacles in the course of their relationship, including Tom’s mother who’s done everything she could to keep them apart. When I began the series, I had an arc in mind for them, which is still playing out in my current (as yet unnamed) work in progress.

The details of fabric restoration, as well as the lacemaking, are fascinating. Can you talk about your research on this part of the book?

I operate on the principle that what sparks my curiosity will appeal to readers. I’m glad to know it did in your case, Robin. I’ve always been interested in antique clothing—the past/present thing again. Garments that people actually wore are a tangible and very personal link to the past.

Several years ago, I visited Greenway, Agatha Christie’s summer home in Devon, England, which is now a National Trust property. The day we were there was quiet with few visitors. Fabric conservators were actually working on one of Dame Agatha’s dresses, and they were kind enough to answer my many questions about their work. Later, at home, I did lots of research into the various methods conservators use. One of the big issues is the removal of dirt and stains. Some are historically significant—blood on a fallen soldier’s jacket, for example—and must not be removed.

I learned about the lacemakers of Devon at a wonderful little museum in Honiton called Allhallows Museum of Lace and Local Antiquities. The day we were there a woman was demonstrating the process, which is so intricate and time-consuming that really only hobbyists attempt it today. Each part of England had its own distinctive style of lacemaking. Honiton lace from Devon, for example, is made by creating individual motifs which are then joined together in a dense overall pattern.

I was fascinated, not only by the process but by the lives of the lacemakers, which were wonderfully presented. Again, I followed up with lots of research at home, and the woman I met at the museum agreed to answer any subsequent questions I had. I’ve thanked her and others who helped me in the book’s Acknowledgments.

Your books are set in England, but you live in Ohio. I’m sure you travel to England, but how do you ensure you are getting the details correct? Do you have English readers vet your manuscripts?

I am lucky to be able to spend time in England every year (we’re going again in October), but as an American, I still need help getting the details right. That’s where research comes in, but I also depend upon beta readers and various experts. For A Collection of Lies, a writer friend, Marni Graff, introduced me to Joyce McLennen, longtime personal assistant and typist for P.D. James.

She was kind enough to read the book, and she taught me something I didn’t know: British people never use the past participle “have gotten” as we do in the States. Instead, they say, “have got.” I’ve heard this, of course, but it never clicked until Joyce pointed it out. I’ve also been fortunate to receive help from specialized sources such as the British police, the coroner’s office in Suffolk, the National Trust, and various experts in medieval documents. People generally are happy to answer questions. If they aren’t, I just thank them for their time and try someone else. For my first book, A Dream of Death, I asked Val McDermid for a source in the Scottish police, and she introduced me to the senior officer on the Isle of Skye.

I was also fascinated by the history of the Romanis in your book. When you have so many rich historical threads to follow, how do you winnow them and not head down a research rabbit hole?

Trust me—I’ve been down a lot of rabbit holes! I love research and often have to remind myself that enough is enough. Readers don’t need all the details—just enough to fire the imagination. What ends up on the page is usually only a small percentage of what I learn. But you bring up the English Gypsies, the Romanichals. They are a distinct ethnic group, only marginally connected with the Roma in the United States.

Knowing that I needed information, I contacted the Romany & Traveller Family History Society in the UK. They suggested I get in touch with Dr. Thomas Acton, a retired professor of Romani studies, himself a Romanichal. He turned out to be a fascinating and very kind man—an OBE and one of the leading experts in the UK on the Romanichals. He agreed to read my manuscript and shared lots of insights. Actually, he was the one who explained that Romanichals don’t consider the term gypsy to be a racial slur as the Roma in the U.S. do. They are proud of the name as their forefathers died for it.

This was a very complicated mystery, with many threads to follow for the reader. Can you talk about your plotting process?

I’m what is sometimes called a “tent-pole plotter,” meaning that I begin a novel knowing the major plot points, but not how I will navigate from one to the next. That’s where the fun of writing comes in, and I’ve often changed my plot to accommodate one of the characters who didn’t want to cooperate with my plans. Plots often develop organically. The tricky part, as you say, is getting all those threads to untangle at the end.

Antiques dealers who carry jewelry as did my parents often have to untangle huge knots in gold chains. It’s time-consuming and meticulous work and can appear impossible. That’s a little like untangling all the plot threads, one link at a time. One of my favorite parts of writing is handling all the plot threads, but I have a confession: In every book I’ve ever written, there comes a time (usually when I’m about three-fourths of the way through) when I throw up my hands and say, “Nope. This isn’t going to work! I can’t do it!”

But there is a way, and I’ve always found it—so far.

Do you consider this series more of a cozy or a traditional series? I think the book has elements of both. Cozy adjacent? What are your thoughts on this type of categorization?

I like that term “cozy adjacent.” I’ve called my books “traditional mysteries with cozy characteristics.” Although I read and admire lots of different kinds of crime fiction, I’m personally not interested in writing graphic language, sex, or violence. It just isn’t my style. I like to think I’m following in the footsteps of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. I love rich settings, fully realized characters, and interesting, twisty plots.

Finally, can you talk about a book that was transformational for you as a reader or as a writer?

Yes, I can! When I was around 11 or 12 (I think), I used to take the bus to the downtown library in my smallish town. I’d spend the afternoon just wandering through the stacks and picking up random books that interested me. The librarians must have been very tolerant because they told me not to reshelve the books but to put them on the returns cart for them to reshelve. I admit I didn’t always do that.

Once I happened to pick up one of the Jeeves & Wooster books by P.G. Wodehouse. I read the whole thing right there and then. The kind of dry British humor he wrote I’d never heard in my life. No one I knew talked that way. I really thought I had personally discovered a writer no one else had ever heard of, and I went on to read almost everything Wodehouse wrote.

I still read his books every year and never get tired of them. They are just so much fun. They still make me laugh. Wodehouse was transformational for me in almost every way as I went on to major in English literature in both college and graduate school. I attended St. Clare’s College, Oxford, where I studied the modern British novel. That’s where I really fell in love with the British Isles, but I believe I became an Anglophile when I first read Wodehouse. And I’ve never gotten over it. When I decided to write a mystery, it was going to be set in the UK—that was a given.

Connie Berry, award-winning author and former aspiring archaeologist, expertly weaves her passion for history and antiques into the Kate Hamilton Mystery series. Set in the UK, the series mirrors Connie’s own unique upbringing and loved for the British Isles, gained through her studies at Ohio State University, Germany, and Oxford, England. Her debut, A Dream of Death, won the IPPY Gold Medal and became a Silver Falchion and Agatha Award finalist. Residing in central Ohio and Northern Wisconsin with her husband and dog Emmie, Connie invites readers to explore her world at connieberry.com.

Robin Agnew is a longtime Mystery Scene contributor and was the owner of Aunt Agatha's bookstore in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for 26 years. No longer a brick and mortar store, Aunt Agatha has an extensive used book collection is available at abebooks.com and the site auntagathas.com is home to more of Robin's writing.