They said you could see the glow in the sky from as far as Philadelphia. The flames were relentless. Firemen and volunteers raced to the scene, but it was an impossible task. Heroism abounded. Troops were called in. In all, the area south of Wall Street and east of Broad Street was devastated.

We’re in New York. But the year is 1835.

What we’ve described was the Great Fire. It began the evening of December 16th, a night of high winds and cold that took the temperature readings down well below zero. A spark in a warehouse on the corner of Exchange Place and Pearl Street turned the area into an inferno in minutes.

The City firemen had been up the night before fighting two other blazes. Exhausted, they raced to fight this new threat.

Because of the intense cold, both rivers were frozen. Firemen had to use their axes to chop holes in the ice, and once they started pumping, the water froze in their hoses. Even vessels in the harbor were not safe. It took two weeks for the fire to be vanquished.

The commercial district of the City was destroyed. Yet, business continued. The New York Stock Exchange resumed trading four days after the fire began. Amazingly, only two people died.

The fire still smoldering, real estate prices for the burned out lots in the district skyrocketed.

Rebuilding began immediately. A year later, the entire area was thriving. Without the help of Congress. It was the New York State government in Albany that approved six million dollars for disaster relief.

The fire that began on September 21, 1776, destroyed one-fourth of New York’s buildings.

In the dead of night, on September 21st, 1776, a firestorm hit the City with tremendous force. It did not come from the shelling from the British ships in the harbor because the British had already—more or less—won the City. Terrified shrieks of women and children rose above the blaze as hundreds of people clutching their few possessions ran from the heat and smoke.

The fire began at Whitehall Slip and burned through Bridge, Stone and Beaver Streets destroying everything in its path, then crossing Broadway, it reduced Trinity Church to ashes. St. Paul’s, only six blocks north, was saved thanks to a bucket brigade of British soldiers and seamen.

One-fourth of the City’s structures were destroyed.

On November 16, 1776, the British took secure possession of all of Manhattan, and the City swarmed with Crown Loyalists from the other colonies. The occupation was painful for ordinary New Yorkers. Soldiers attacked young women, looted and pillaged, seized livestock, cut down forests and shared nothing with the freezing, starving people. New York remained in British hands until November 21st, 1783. The British left the City in terrible shape. They had not rebuilt the area destroyed by the fire years before. Trinity Church remained a burnt-out shell. Buildings still standing throughout the City were unlivable. Private homes had been made foul. The now treeless streets were clogged with filth and garbage.

Any other city might have been whipped, but we’re talking about New York.

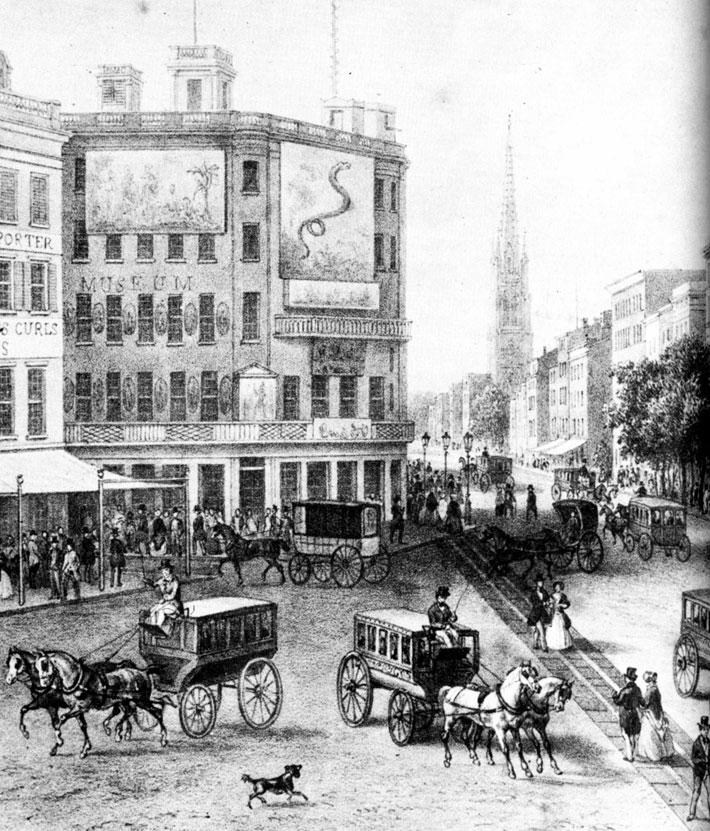

Confederate officers set a fire in Barnum’s Museum on Broadway (center; St. Paul’s at right).

The plot to destroy New York began in the fall of 1864. Even though the Confederacy was on its last legs, Judah Benjamin, its Treasurer, allocated $300,000 for the mission. Its purpose was to demoralize the North by burning down its most important city.

The conspirators were eight Kentucky officers. Though Kentucky was a Union state, it had many Southern sympathizers. The eight officers were assured that New York, being a city of commerce, had its share of those who believed in the Cause, and that these would rise up and join the conspirators.

Yes, New York had Southern sympathizers. The war was bad for business. But the conspirators totally misunderstood the people of New York. We complain mightily, but we stand fast.

The conflagration was earmarked for Election Day. Lincoln was running for a second term and New York was an anti-Lincoln, Democratic stronghold. Somehow, it became common knowledge that the conspirators were in the City and the army was called in to protect the election. The conspirators decided to bide their time and choose another moment when the City would be most vulnerable.

While they waited, they attended lectures and concerts and church services, even played baseball in Central Park, mixing freely into cosmopolitan New York life. Truth to say, they got swept up in the magic of the City. The news of Sherman’s burning of Atlantic brought them back to their mission. Swearing revenge, the eight determined to carry out their original plan.

They chose the day after Thanksgiving, which Lincoln, after the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, had fixed as November 24th. Since municipal buildings were now guarded, the conspirators selected as targets thirteen of the City’s finest hotels. Teams went to several of them and rented rooms. They decided that with fires in many of the hotels throughout the City proper, flames would race through entire neighborhoods, causing great panic. In additon to the hotels, fires were set in warehouses and ships along the waterfront, in Barnum’s Museum, Niblo’s Theatre, and the Winter Garden Theatre, where the Booth brothers were performing Julius Caesar to raise money for a statue of Shakespeare for Central Park.

But the conspirators were poor scientists and worse arsonists; they made a crucial mistake. By closing the doors and windows tight, they suffocated their fires. The result was more smoke than fire. Volunteer firemen and the police performed admirably. Although the damage was calculated to be about $400,000, no lives were lost. We’re not surprised that the conspirators, in what newspapers of the day dubbed The Incendiary Plot, were dazzled by the amazing City of New York. We were born here, and the City still has this affect on us.

Return of the American troops to New York, 1783.

In November of 1783, after occupying the City for eight long years, the British, smart in their fine red coats and arms, marched down the Bowery to the East River wharves and out of New York forever. George Washington and his troops returned, tattered, but triumphant.

Once more our City rises from the ashes.

Note: This essay originally appeared in Mystery Scene #76, Fall 2002.

Martin and Annette Meyers, using the pseudonym of Maan Meryers, write The Dutchman historical novels and short stories which span several centuries of New York City history. Their latest book in that series is The Organ Grinder (Five Star, 2008).